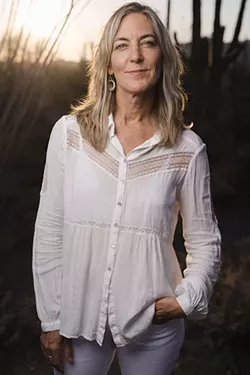

In the 22 years since Kimi Eisele came to Tucson to get a master's in geography from the UA, she's accomplished more than most of us do in a lifetime.

In 1998, she founded you are here: a journal of creative geography, still in print. As a dancer and a choreographer, she directed NEW ARTiculations modern dance company, memorably producing FLOW, a dance about water that was performed in the (then!) dry Santa Cruz riverbed, and a Rosemont piece, danced and filmed in the Santa Ritas, about the devastation the open pit mine would wreak on animals and plants.

She's a visual artist who makes photos, cut-paper work and puppets, and a performance artist who won a National Park Service commission to create the multi-disciplinary Standing with Saguaros. A longtime teacher and editor, she's also a writer who's published work on the arts, the border and the environment in national publications. Right now she works at the Southwest Folk Alliance, helping to preserve "traditional knowledge and cultural expression."

This week, Algonquin Press launched her first novel, The Lightest Object in the Universe, a post-apocalyptic story of love and community. The book has already garnered multiple honors: among other awards, she was named a Great New Writer by Barnes & Noble and the book was declared one of the Best Reads of 2019 by Powell's Books. Publisher's Weekly called it an "intense, moving romance" and a "smart debut." Library Journal praised its "luminous writing and messages of love and hope."

Below is an email conversation with the Tucson Weekly.

Your book was just released on July 9, but even before it was published it got a lot of buzz. Pretty heady for a first-time author! Why are people drawn to it?

For as much as we fear death in this culture, we North Americans are fascinated with the end times. Just Google "post-apocalyptic movies" or "post-apocalyptic fiction." But the past two decades have given us plenty of real-life brushes with dramatic, often horrific events that seem to portend some kind of ending for life as we know it. For people living under siege and amidst war, the apocalypse is every day. The climate crisis, combined with human greed, is quite literally ending many species right now. I set out to investigate what happens when the Superpower is, in fact, stripped of all its power. What will survival look like? How will we re-imagine power? I think many readers are drawn to the book because of those questions. Also, the cover of the book is beautiful. I lucked out.

In the first chapter, excerpted here, Beatrix and Carson cope with a failed world economy, collapsed governments and a burned-out electrical grid. Yet in this post-internet, post-cell phone world, love persists and communities work together. Would you agree with the reviewers who've called it a hopeful post-apocalyptic novel?

I would agree. From my other work, you know that I tend to look for solutions and goodness, and I lean towards beauty because there are enough problems and pain to fill lifetimes. Of those long lists of dystopian books and movies, very few focus on the light. It's true that we can't know sorrow unless we know joy, right? I didn't want to write more of the gloom and doom. In fact, I couldn't. I had to go back many times and add more death and menace and destruction to the novel. Early readers joked that the book was too "Sesame Street." Not that everything was joyful on Sesame Street—I mean, Oscar the Grouch! I sometimes correct people who label the novel "dystopian." It's really "utopian," if that's what you call looking to your neighbors as friends and deciding to help one another.

Carson embarks on a cross-country hike in hopes of finding his beloved. He walks the nation's abandoned railroad tracks, following the path of the hobos of the 1930s. Did you have the Depression in mind when you shaped his journey?

In part, yes. Mostly the train trope came from Tucson: my bicycle commutes across the tracks, waiting for trains to pass, watching graffiti roll by. I began to imagine the rail as a trail, and eventually I came to 1930s accounts of hobo travelers and a zine made by present-day train hoppers. There is a whole hobo lexicon, poetic and useful: "Jungle," for example, is a term for hobo camps, which I used. Carson also creates his own moniker, "The Professor," to mark his presence along his route. I read Studs Terkel's amazing oral history, Hard Times, about the 1930s Depression to glean the mood of that time and also the sense of resourcefulness. We were once much less wasteful, and perhaps more cooperative too, in some ways. I hope we can return to that.

Beatrix jumps in to help her community in the wake of the disaster. Your own neighborhood, you wrote in an essay, is filled with people who ride bikes, raise chickens and plant gardens. Did Tucson serve as a model for the book?

Very much so. When I started the novel, I was living on the west side, in Menlo Park, and bikes and chickens and gardens were all around me. Goats, too! Those practices had been part of life there for generations. I later moved back to Armory Park, where I lived on and off for nearly two decades. I met so many of my neighbors while walking my dogs. When crime happens there, which it often does, neighbors really look out for each other. It helps when you have people like Janet Miller invested in bringing strangers together through public life and everyday beauty. (Have you been following the abandoned OK Market? It's practically a thriving neighborhood café now!) I recently moved to a new-to-me neighborhood. I feel a little overzealous, shouting "Hello!" to all the other dog walkers. I hope they'll warm to me.

You've been working on the book for years. How did it change over time, as the political scene shifted in the U.S.?

Years, it's true! The book didn't change that much at its core, it just got more relevant. In early drafts, I kept the causes for the collapse vague—a mishmash of trade imbalances, the end of oil, flu, terrorist attacks, natural disasters. My editor pushed for more specificity. I read Ted Koppel's book, Lights Out, about how vulnerable we are to a cyberattack, which scared the crap out of me and also offered a very plausible way for the grid to topple. When the 2008 financial crisis happened, I thought, "This is all coming true." I sold the book shortly after the 2016 election, which for me heralded a very real sense of doom. Early in the novel, there's a scene where a teenaged boy is describing the events of the unraveling by interpreting aloud graffiti on the walls of an abandoned building. One artist has rendered the collapse of the grid with a giant splotch of orange and then darkness. That was my subconscious at work.

You've had an unusual multi-genre career. How did you create that life and still pay the bills?

I had miraculously cheap rent for a long time. Tucson has been good to me. I have long lived off freelance writing, teaching, and research gigs, with a few good grants thrown in. For a short spell, I had a full-time job at a public relations firm. They didn't like that I went home for lunch to let my dogs out. They also didn't like that I sometimes took off my shoes at my desk. It's hard to corral a freelance artist, I guess! One thing the novel has taught me is the value of social capital, and how much of it I have, given my work over many years in this community. My characters learn—as I have learned—that survival is about access to water, food, and shelter, and that sometimes those things don't come from cash or credit, but from barter and kindness. I now work for the Southwest Folklife Alliance, with amazing colleagues who are equally invested in upholding and spreading the ethic of community benefit and equity.

What's next for you?

I just attended an oral history institute at Columbia University, so I'm thinking a lot about interviewing and documentary work, especially in this era of false narratives and lost species. Can you do an oral history of another species? An artifact? What about an ethnography of a forest? I am working on another manuscript, part memoir, part novel. It features animals and trees and sometimes they need to say things, as do the dead. "Who says that's fiction?" a Hopi basket weaver asked me recently. Indeed. ■