Back in the spring, Kareem-Anthony Ferreira prepared an array of large-scale paintings to present in the MFA show at the University of Arizona.

The canvases, lush and gorgeous, portray the members of his extended family, Trinidadians who immigrated to Canada and their first-generation Canadian offspring. The young Black artist, born in Ontario, grew up in these dual cultures. In his art he aims to make a "visual re-creation of both identities" and to skewer stereotypes about Caribbean "island life."

His big works, a mix of oil paint, wax crayon and collage, were to be hung at the UA Museum of Art in the spring, alongside art by some 10 fellow MFA grads. Then, of course, the coronavirus hit. The planned in-person show was reduced to an online exhibition, and I got my first look at Ferreira's epic works by squinting into my tiny laptop.

Months later, in early October, I was elated to find one of Ferreira's exhilarating paintings at the Tucson Museum of Art in the "Arizona Biennial 2020." Given pride of place at the entrance to the big show, his work, "The Same Restless Energy, Mischief," 2020, huge at 5 ½ feet high and more than 11 feet wide, is as grand as any 19th-century painting of royalty or shipwrecked sailors. His figures, loosely painted in rich colors, are lionized by the magisterial canvas. Clearly, their lives matter.

In the painting, a trio of Black adults, two of them dressed in the brightly patterned clothes of the Caribbean, are hanging out on a bench in a park shimmering with green grass. Beside them a restless little girl squirms in her chair, eager to be on her way. And in a second, attached panel, another young girl is galloping on a stationary play horse, itching to ride off into her life.

The Biennial, an every-other-year juried show of Arizona artists, was delayed by COVID-19 but TMA was adamant that the show go on, with health protocols in place. This year's guest curator, Joe Baker, a Native artist who directs the Mashantucket Pequot Museum in Connecticut, winnowed the 1,351 entries down to 88. Tucson artists made a good showing, as usual, and there's a robust variety of voices—from Black and Native, to Latinx and White.

It's a pure delight to see art in person, after months of virtual exhibitions, and the show is a cavalcade of art genres.

Among the abstract works, Katherine Monaghan's elegant rust and acrylic on paper stand out, and so does Tucson's Jeffrey Jonczyk's "Wine" acrylic on wood.

A super realistic painter, S. Jordan Palmer of Prescott, teases our town in an oil on canvas slyly named "I Dream of Tucson." The beautifully painted work pictures the Old Pueblo at its most poverty-stricken: it pictures an ugly old mattress jammed into a dumpster. Nevertheless, says Dr. Julie Sasse, the museum's chief curator, it is museum patrons' favorite piece in the show.

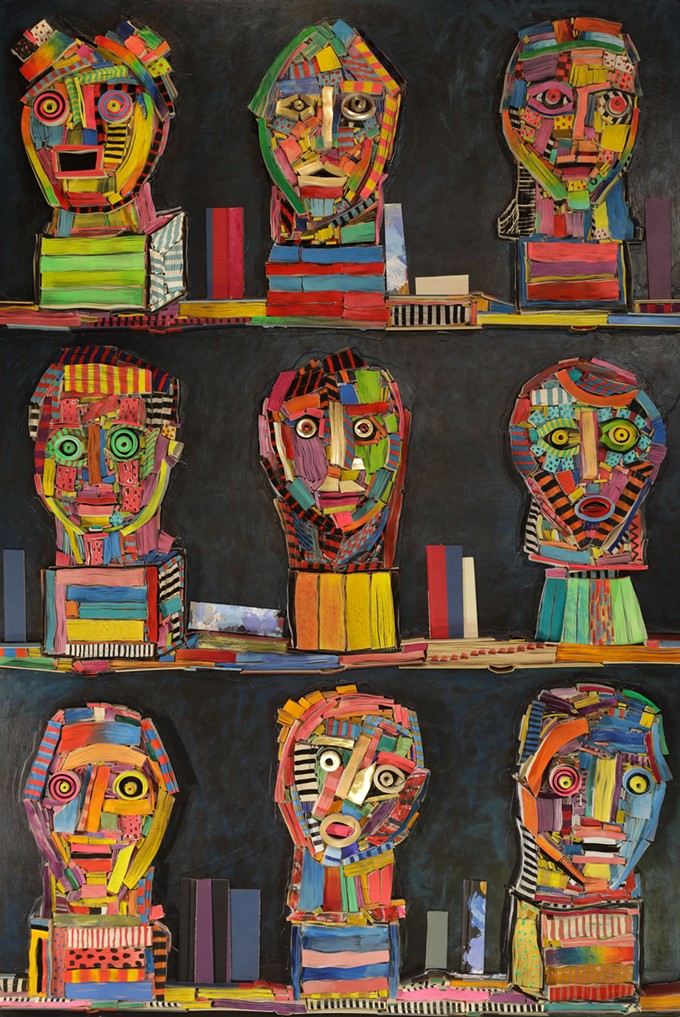

In the category of unusual media, Jessica James Lansdon has laid a delightful table of small shapes made with clay, salt dough and "slime," and arranged them strictly by their twinkly colors, pink, blue-green, yellow and white. Jo Andersen used "roadkill snakeskin" and paper made from desert plants to create a 3D "Book of Snakes." Nick Georgiou puts nine gloriously colored heads on his "Credibility Bookshelf." The picturesque heads are cleverly crafted from the pages of old books.

Julia Arriola laments the murders of Native women in an installation of tribal dresses. Mia B. Adams made a challenging video in which she makes a layered cake of the troubled U.S, complete with icing. Her title? "Freedom Has Never Tasted So Good."

Not surprisingly, in a contentious year in which 215,000 Americans have died from an uncontrolled virus, when police killings of Black people have triggered outrage and protests around the country, and when desperate migrants and asylum seekers have been treated cruelly and often illegally, there's a lot of political art on view.

The Border Patrol, and the entire Trumpian immigration regime, come in for well deserved criticism. Two artists made sculptural works evoking the infamous kids in cages, the thousands of migrant children, including babies, who were ripped out of their parents' arms by Border Patrol. ("We need to take away the children," Jeff Session, then the U.S. Attorney General, told prosecutors in 2018, according to a preliminary report by the Justice Departments' own inspector general.)

Nathaniel Lewis, from Phoenix, responded to this travesty by creating "Detention," a cage that looks a little like a child's playpen, with bars cheerfully painted bright red, yellow and green. But the space is covered in wire, and a small child is trapped inside, sitting numbly on a stool, its face pale and empty.

In "Hope Confined, Dignity Suppressed," Tucson artist Perla Segovia made a wiry cage; tiny shoes lie on floor. She also embroidered a toothbrush and soap, hygiene items that a Justice Department lawyer argued in court were not essential for incarcerated children in crowded Border Patrol prisons.

(The judges were appalled

Another Segovia work, "Immigrants' Void," 2018, a watercolor on embroidered canvas, is a portrait of a family separated from two daughters. The missing girls, colorless, hover like ghosts among their loved ones.

Nogales native Steffi Faircloth, a young artist now living in Tempe, made a video of a creepy agent making a car stop. Alex Turner, of Tucson, photographed a darkened desert trail, where terrified migrants and asylum seekers may well lose their lives. (Migrant deaths have skyrocketed in this year's brutal summer. The toll for 2020, from January to Sept. 30, is 181 deaths, a big jump over last year's 144 deaths at this time of year.)

No wonder Mia B. Adams made that angry cake. And no wonder Paul Abbott, a mild-mannered English transplant who lives in Arizona's Skull Valley, painted a giant angry guy in "Useless Wall," a big beautiful classic oil on canvas. The guy, perhaps incensed by the government's billion-dollar project to destroy some of Arizona's most beloved wild sites with a monster border wall, just stands up and screams. What else can he do?

But art does offer comforts. "Memory and Loss," from Olin Perkins, born in Sacaton, in the Gila River Indian Community, is a meditative head, carved from wood and painted in oils. This traditionally inspired work reminds us that life has always been hard, filled with losses, but the memories of those who fought for justice can embolden us to act.