A week after Sept. 11, Semezdin Mehmedinovic took off on a 10-day journey by train. He quietly slipped out of his adopted Alexandria, Va., and spiraled through Washington, Chicago, Los Angeles and back through Chicago and Philadelphia before returning home.

Nine Alexandrias poured forth from his trek--a spare, 30-prose-poem text reveling in the paradoxes of American culture. One of the poems, "Open Dialogue," details seemingly innocent questions from a fellow train passenger, but also maps more than mere geography.

'Where are you from?

Bosnia

Serbs and Croats, right? Is anyone else there?

There are others.

What color are your eyes?

Green till Colorado/But since we passed Apache Canyon/They're blue in the/New Mexico light.

So then what kind of Muslim are you?

White.'

Mehmedinovic, it seems, took this trip to make sure the world was still in one piece. His freedom to jaunt around the American landscape was not something he experienced in Sarajevo--his capital city pummeled by war.

He's shaped by that war, the second generation of intellectuals to emerge from the former Yugoslavia. Born in 1960, published by the time he was 24, the Bosnian poet not only survived the eruption of hostilities in 1992, but he stayed to write about it, to mirror the incendiary battles exploding around him, to believe that Kosovo would be an isolated case of state terrorism, to organize film festivals while shells were falling all around him.

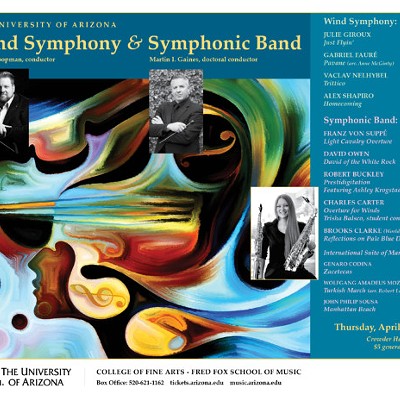

He has written five books, worked as a columnist and editor of the magazine Phantom of Freedom and was the co-writer and co-director, with Benjamin Filipovic, of Mizaldo, one of the first Bosnian films shot during the war. His third book, Sarajevo Blues, published in 1995, began as a magazine column. They were "clear, simple messages to send outside of Sarajevo, to explain, 'This is our reality,'" offers Mehmedinovic of the sparse prose framing his experiences of living amid looting, corpses and curfews; politics, intellectuals and war profiteers.

He wrote as a letter to people on the outside, believing it would help change what was going on in his country.

"But nothing changed," he chortles, though someone on the outside got his message.

"One night in 1993, the phone starts to ring. I had forgotten that kind of sound. A voice from the other side says, 'This is Ammiel Alcalay from New York.' (He was) a man born in the states to Balkan parents, who'd read my book and wanted to talk to me about translating it," says Mehmedinovic of the first conversation he had with the translator of both Sarajevo Blues and Nine Alexandrias.

He finally had to leave his home country because, he explains in a 1998 interview, war criminals were brought into the circle of power while poets and literary critics were being threatened with expulsion.

"So by the end of 1995, I really felt like I had lost my cover, that I remained, in some sense completely unprotected. ... Having survived the war, this was not a good feeling to have."

Mehmedinovic fled to the states with his family as a political refugee in 1996. Though he says, individually, he hates politics, he qualifies, "It's important for me to participate as a writer in politics. I'm a witness about present time, though I have three or four different ideologies vying for my attention--my former communist country that only dealt in the future or the past; the bloody, very real Balkan wars; nationalism that only deals with the present.

As an outsider, Mehmedinovic astutely recognizes what's happening to American culture during what he calls "fundamentalist rule" in this country. Growing up in Bosnia, he was steeped in American icons--Kerouac, Ginsberg, Burroughs, Dylan--and films from the 1970s and 1980s.

"I think America is under siege. There's a type of censorship underway. The Constitution doesn't seem to mean much now. You have an amazing democracy here, but there seems to be this intention to destroy the American cultural model."

He adds, "Maybe I'm a political writer, but I'm also metaphysical. I ask important questions about what life is, what death is, where I am in this moment. I'm more like Homer and Dante, but also like Czeslaw Milosz. It's not important to have the actual war experience in order to write about social or metaphysical problems."

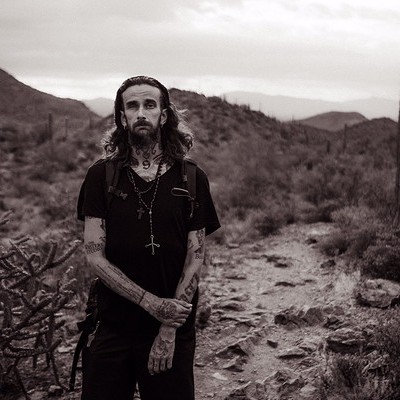

When Mehmedinovic arrived in the states, he spent five months in Phoenix, witnessing many contradictions.

"Can you imagine? I come from the Balkans winter full of snow, war-ravaged, in very bad shape. And I come to this land of sunshine. It was paradise to me," he grins.

"It's what I wanted at that moment: real society, real institutions. When I came here, I arrived in a society with a huge level of freedom, but I saw so many social problems, micro-wars, really."

Mehmedinovic has pondered extensively what happens to art during wartime comparing various geographies. He says in Bosnia or the Middle East, cultural dialogue keeps apace with the crises. But in the states, he explains, politics keep the arts in its shadow.

He's been back to Sarajevo only once in the nine years he's lived here, though he stays in daily contact with friends there via phone or e-mail. He admits he's not sure it's a good place for him to go. His first book as an exiled writer has a certain feel to it, an outsider peering in.

"The next book I write, I will be less of an exile. Maybe it will be funnier, more American."