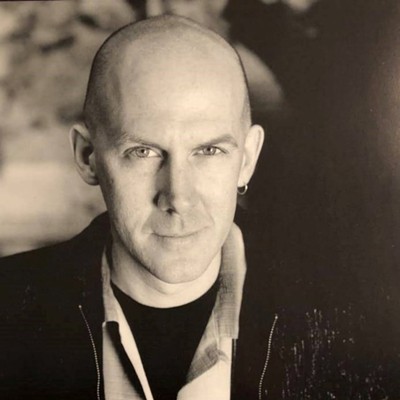

Several years ago, I wrote about Uncle Al in a column here in The Weekly and in an article in Sports Illustrated. It was a story of misfortune and injustice, and ultimately, one of integrity. His passing reminded me of how things used to be--and just how bad things have become.

Uncle Al graduated from Mason City (Iowa) High School in 1941 and enrolled at Creighton University in Omaha on a football scholarship. About a month after his freshman football season was over, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. Like most young men of his generation, he marched off to war without giving it a second thought. However, since he was a "college man," the military decided to send him to officers' training school.

He was sent to Bowling Green University, where he lived in a shadowy world that was neither full-time college nor all-out military. He took a makeshift load of college and military courses and found time to work out with the school's football team.

The college landscape was chaotic. Go through any major college's media guide, and you'll see that the schedules from 1942-45 were cut short or cancelled altogether, and those teams that did play often competed against the likes of the Great Lakes Naval Base or Fort Huachuca. It was in this topsy-turvy situation that Uncle Al "competed" for Bowling Green. He quarterbacked the team for all of one season and part of another before the military finally shipped him to the Pacific.

Decorated for his bravery, he was kept in the Pacific by the military for 18 months after the war was over. When he finally returned home, he enrolled at the University of Iowa, where he immediately won the job of starting quarterback for the up-and-coming Hawkeyes. He played well his first year there, and in his second year, Iowa challenged for the Big 9 title. (Northwestern hadn't yet joined the conference now known as the Big 10.) Newspapers touted the passing combination of Al DiMarco to (future NFL Hall of Famer) Emlen Tunnell, whom they indelicately referred to as "The Negro Flash."

After his second year at Iowa, Al DiMarco received lots of postseason accolades, and many felt that he had a chance to be the best quarterback in the country the following season. But just before that season was to begin, the Big 9 informed him that he would not be allowed to play anymore. They had decided to count his seasons at Bowling Green as collegiate participation and, therefore, he was out of eligibility.

The decision was ridiculous for two big reasons. First, the entire nation was liberally sprinkled with athletes who had played before and during the war and then returned to college after having served their country. Using the criteria that had been arbitrarily leveled at Uncle Al, that same year, Ohio State had four starters who were in their sixth year of competition, while Notre Dame had two guys who were in their seventh year of college ball. Furthermore, if they were going to count the years at Bowling Green against him, they shouldn't have allowed him to play the previous year, which would have been his fifth under their capricious system of counting.

The worst lawyer in America could have won the case in court, but, as Uncle Al told me, "Things were different back then. You didn't think about suing. You believed that people were doing the right thing, and you didn't really question their motives."

He finished up his schooling, got married and started a family. He became a teacher, football coach and athletic director at Dowling Catholic High School in West Des Moines, where he stayed for 40 years until his retirement. When Lute Olson was at Iowa, he recruited Bobby Hansen from Dowling, and he remembers Al DiMarco as a man of decency and charm.

When Uncle Al retired, his son, Danny, tried to get the Big 10 to grant his father an honorary extra year of eligibility. The then-Big 10 Commissioner, Wayne Duke, decided not to do it for fear that others would want similar treatment. As Duke weakly explained, rubber-stamping the injustice of 40 years earlier, "With all the lawsuits these days ..."

The day Uncle Al died, there were articles in all the papers about the lawsuit filed by former Ohio State running back Maurice Clarett. Last year, freshman Clarett helped lead Ohio State to the national championship, but, as is often the case these days, he could find the end zone, but couldn't seem to find his way to class. Last spring, Clarett managed to get in trouble with the school, his team and the law.

Clarett is in court these days trying to force the NFL to drop its ban on drafting anybody who isn't at least three years out of high school. The NFL is fighting him hard, because it doesn't want to go the route of the NBA, a league full of underage, unskilled jackasses who don't know how to play the game.

Clarett will probably win the suit, opening up the floodgates for a gang of immature thugs to storm into the league and further dilute the once-great product (such as it is in these days of end-zone cell-phone celebrations).

The Clarett story got big ink, while Uncle Al's obituary was tucked away in a corner. They did mention that he had quarterbacked Iowa and had held several school records for a time.

Back in the late '70s, when I was playing college ball, I had a chance to talk to Uncle Al, and he noticed that sportsmanship and honor were starting to slip even then. But, he told me, "Times change, but right and wrong never does."