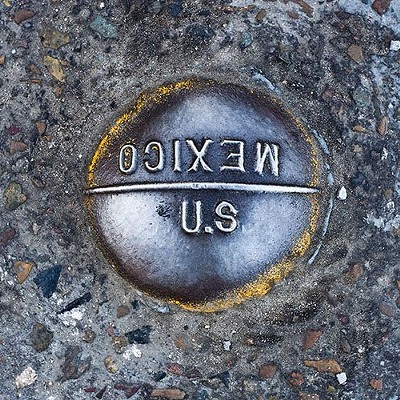

From the forthcoming book: Border Patrol Nation: Dispatches from the Front Lines of Homeland Security by Todd Miller | City Lights Publishers, March 2014

It is 6:00 a.m., and there is a loud pounding on the door. Gerardo looks to Luz, who is also suddenly jarred awake, and both get up quickly. He is in shorts and an undershirt. It is a cold March morning in Tucson, Arizona. Across the bedroom is a bunk bed. Somehow Adrián and Sammy are sleeping through the loud pounding. Adrián is twelve and Sammy is ten, and both, it seems, can sleep through a war. Gerardo looks out the window. There are armed men out there.

"Okay," he tells Luz, "they are coming for me."

Gerardo opens the door. Outside there are six agents from Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)—a division of the Department of Homeland Security like the Border Patrol, but with a focus on internal enforcement. Minutes earlier, Gerardo and Luz were sound asleep in their bedroom. Now they are both disoriented, somewhere between awake and asleep. It is so early that there isn't even a hint of the sunrise. Luz listens with her heart racing. The men outside are just shapes with flashlights and guns.

Similar to military operations, predawn house raids have become a routine tactic for ICE. It's a time when people are at their most vulnerable: at home and likely asleep and defenseless.

While post-9/11 immigration geopolitics has mostly focused on the Mexico-U.S. border, writes geographer Mat Coleman, "perhaps the most significant yet largely ignored immigration-related fallout of the so-called war on terrorism has been the extension of interior immigration policing practices away from the southwest border." Immigration raids have been going on for decades, but the current political climate has created a new scope and intensity for ICE, an agency that, like CBP, has seen an unprecedented flood of resources and funding. These resources are behind not only enforcement operations such as the one at Gerardo's house—programs with thousands of police and jails nationwide—but also the creation of the largest detention and deportation regime in the history of the United States.

Before 1986, the number of annual deportations in the United States rarely exceeded 2,000. It was that year, with the passage of the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA), that the seeds for big changes were planted. IRCA was the first bill to define some crimes as deportable offenses. Perhaps this change seemed like a small addition to the law—more popularly known as a reform bill that brought legalization to hundreds of thousands of unauthorized people in the United States—but it wasn't. It provided the legal blueprint for a deportation regime that would only become more massive. The 1996 Illegal Immigrant Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act considerably expanded the number of crimes considered deportable, launching a new system of banishment that would impact millions of people. By the late 1990s, the U.S. government was deporting more than 40,000 people annually, still only a fraction of what we see today. By the early 2010s Homeland Security was expelling well over 400,000 people per year from the United States. "One of history's most open societies," according to historian Daniel Kanstroom, "has developed a huge, costly, harsh and often arbitrary system of expulsion."

The U.S. deportation regime is an efficient and finely tuned governmental monster that seems never to be satisfied but is always hungry for more human fodder. Blurring the boundaries between the militaristic and the bureaucratic, it is a coercive force that rules from above with discretion, violence, and military-style tactics, as seen with the ICE raid on Luz and Gerardo's home. It is also a "political-economic power" that is "anchored by relatively steadfast legal and administrative practice," as Mat Coleman told me in an email. In other words, according to Coleman, "there's no hard boundaries here between infrastructural and despotic powers, even though there may be important differences." The monster is a legitimized army of bureaucrats and "soldiers" in a promiscuous relationship.

Disoriented, twelve-year-old Adrián wakes up and looks into the jaws of this monster. There is a window by the bunk bed. He looks out and sees his father, Gerardo, surrounded by uniformed agents in the parking area outside their Tucson apartment. What happens next is an image Adrián will never again be able to shake from his mind. He sees an ICE agent telling his father to turn around. He sees an ICE agent handcuffing his father. It is still dark out. He sees his father being forced into a white van. His crime: using a false Social Security card in order to work.

"Mom," Adrián yells in the dark, "it's a white van." He yells it as if his father is being kidnapped. Luz rushes to the window, looks out, and sees the ICE vehicle backing out fast. Adrián looks at her intently as if they could track the van down and get his father back. There is still a chance. They can still hear the vehicle. When he sees his mother's shocked, panicked, and saddened face he explodes into tears. Neither of them has any idea about what might happen next.

Hidden in Plain Sight

The west Manhattan neighborhood of Chelsea is known for its vibrant arts scene, its gourmet food, and its high-end residences. It is also famed for the long-abandoned elevated train line that city officials have converted into a one-mile park, the High Line, that slots through a canyon of buildings containing blue-chip condos, art galleries, and expensive office spaces. As I walk around, it's hard to imagine that ICE would be concealed amidst all this high-end chic.

The epicenter of this neighborhood is the bustling Chelsea Market, located in a refurbished five-story brick building where the New York Biscuit Company invented the Oreo in the 1950s. Three stories above Chelsea Market is the office of the U.S. Marshals Fugitive Task Force, the workplace of A&E reality TV star and ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations supervisor Tommy Kilbride. The office's rise to reality television stardom is no surprise, given its location in the heart of the New York media empire.

Kilbride himself was a Border Patrol agent for four and a half years in San Diego before joining the Immigration and Naturalization Service in 1995. He says he is an early riser, and makes sure he gets to the office before anyone else, because he wants "to make the world a safer place to live." Kilbride's role as a star in Manhunters: Fugitive Task Force, he asserts, has brought the "valuable" work of ICE to the national imagination.

Kilbride has a no-nonsense tone, underscored by a Brooklyn accent. In one of the show's episodes the agents go after a Jamaica-born man who "snuck back into the country," according to Kilbride, "an illegal re-entry." Kilbride lets viewers know that it is not acceptable that this "seven-time convicted felon" is roaming the streets of his native Brooklyn.

The episode opens with a panoramic shot of the Manhattan skyline under a dark cloudy sky, setting the scene for the predawn raid. It is 6:15 a.m. when the six-person task force arrives at the entrance of a brick apartment building in Brooklyn. Snow is slowly falling, giving a graceful look to this quiet part of the morning. The tranquility quickly dissolves when they enter the building. The music gets dramatic, tense, and anxious. In the background you can hear a heart thumping. The camera pans onto a solitary black door and slowly zooms in. One of the ICE agents silently mouths to the rest of the group: "Somebody is at the door." The camera focuses on the hand of an agent clutching the handle of his holstered gun.

Although the impression is that the worst criminals in the world lurk on the other side, the officers politely knock on the door, as if they were visiting an old friend at midday. However, according to findings of a 2009 report, Constitution on ICE, by the Cardozo Immigration Justice Clinic, this detail is inaccurate. ICE agents rarely knock on the door. They pound, and they pound hard. The authors analyzed hundreds of cases of house raids in New York City and the surrounding area. If a person voluntarily opens the door, even just a crack, agents force their way into the person's residence, most times with no judicial warrant.

In one case on Long Island, agents like Kilbride entered the bedroom of a sleeping woman, pulled the covers off the bed, and shined their flashlights onto her face and the face of her child, who immediately began wailing with terror. In another case on Staten Island, armed ICE agents entered the private bedroom of a man, forced him into a hall, and made him stand in his underwear before his brother, his sister-in-law, and their children while they searched the residence. Around the same time in Massachusetts, ICE agents burst into a three-family apartment building by kicking through the front door, leaving splintered wooden fragments on the floor. As in a war, they commanded everyone to lie down and stay still. They shined bright lights directly into each person's terrified face. They forced open more doors as well as a safe. They left the safe open, its contents and papers strewn around.

There were other cases of agents standing above people while they are still in their beds and barking things at them like "Fuck you!" and "You're a piece of shit!" In response to such abuses, immigration judge Noel Brennan said: "It is hard for me to fathom a country or a place in which . . . the government can barge into one's house without authority from the third branch."

In the episode of Manhunters, however, Kilbride and his crew have a made-for-TV judicial warrant to search the home of the Jamaican man's wife. When they capture him in Queens, Kilbride turns to the camera and says, "This is Lloyd [the Jamaican man's name]. He's done." Kilbride says this with the confidence that they are right to remove this man from the country, as well as the other 400,000 people they will deport. To the public, they are fulfilling their mission of promoting "homeland security and public safety."

When walking through the Chelsea market—through its gourmet food stalls and high-end coffee shops—you don't even know that such a national security effort is constantly in progress right above you. Across the street from the Marshals Fugitive Task Force office are the restaurants of two of New York City's most prized chefs, who also have their own reality TV shows. Mario Batali stars in ABC's daytime show The Chew, and Tom Colicchio tops the bill in Bravo's reality cooking series Top Chef. Above their restaurants—Batali's Del Posto, where a seven-course meal goes for $145, and Colicchio & Sons, where a white asparagus salad is priced at $23—is another one of ICE's unmarked offices, this one for a counterterror joint task force. ICE is everywhere, and who would ever know?

This is just one of 186 unmarked ICE facilities as of 2009 that political scientist Jacqueline Stevens highlights in an article in The Nation. These secret locations exist in addition to ICE's listed field offices and detention sites. Some are located in strip malls and office complexes, places that seem so normal to everyday life in the United States that one wouldn't suspect they are government sites where armed federal authorities detain and interrogate people. It could be the Chelsea High Line. Stevens quotes Natalie Jeremijenko, a professor of visual arts at New York University, who called it "twisted genius" to hide federal agents here, in the "worldwide center of visuality and public space." But it also could be in a suburban strip mall crammed in between neon-lit fast-food restaurants and retail outlets. Expansive as a retail chain with the budget of a large corporation, a national security necessity to some, a large monster to others, yet hidden in plain sight.

Through the good deeds of Tommy Kilbride in Manhunters and similar "reality" television programs such as National Geographic Channel's Border Wars (which profiles the U.S. Border Patrol), the public can be assured that ICE and the Border Patrol are on the case, and that with the increasing militarization of immigration enforcement, the homeland is protected. The enemy—the ominous "criminal alien"—is presented, cultivated, and sustained in the public imagination. This makes the call for more resources all the easier; without a doubt there are many enemies who are out to get us.

The Feeders

From 2005 to 2012, ICE's detention operation budget more than doubled, rising from $864 million to $2 billion. The agency's detention facilities went from an 18,000-bed capacity in 2003 to a 34,000-bed total in 2011. Five hundred twenty-five of those beds are located in Batavia, New York, at the Buffalo Federal Detention Facility where I meet with ICE Supervisory Detention and Deportation officer Todd Tryon.

Tryon, a former U.S. Border Patrol agent, has a thick brown book on immigration law placed smack in the middle of his desk. Tryon tells me that the Buffalo Federal Detention Facility is "accredited by the American Correctional Association," as if it were a resort or hotel, or some feature you'd see in a guidebook for tourists.

Tryon wears a white button-down shirt and a blue-striped tie. He is balding and has a mustache. The Elmira, New York, native speaks with a Buffalo accent. He leans back in his chair and talks about "feeders," as if the Batavia detention facility were a large, hungry predator. The feeders, those who send people who have been arrested to the Batavia facility, are the Border Patrol, he says, the bridge authorities (CBP officials stationed at the bridges crossing the international border from Canada), and the ICE detainers. The people that CBP arrests are indeed filling immigration detention centers across the country. The ICE detainers underscore a whole new mission. Instead of just keeping people out of the United States, since 1996 they've been deporting people who are already here.

"ICE places detainers on aliens arrested on criminal charges to ensure that dangerous criminals are not released from prison/jails into our communities," ICE spokesperson Nicole Navas explains in an article. "Even though some aliens may be arrested on minor criminal charges, they may also have more serious criminal backgrounds, which disguise their danger to society."

Navas might as well be next to Tommy Kilbride on Manhunter as she describes the "criminal alien" to the greater public, showing how easy it is to fill ICE facilities such as Batavia with violators. It doesn't matter if these non-citizens are unauthorized or legal permanent residents, they are the targets of U.S. government "criminal alien" enforcement programs, which began in the 1990s but are now led by Secure Communities, a high-tech information-sharing program linking ICE, the Department of Justice, and local law enforcement. In 2008, Secure Communities piloted in sixteen locales, but in five short years spread across the United States into more than 3,074 jurisdictions, covering 97 percent of the country.

Of all ICE's internal enforcement programs, Secure Communities is creating the most detainees for places like Batavia. In 2010, for example, ICE issued more than 65,000 detainers. It works like this: if police in any of those jurisdictions book a person, for whatever reason—including loitering, driving with an expired license, a broken taillight, or not carrying identification—their biometric data goes to the FBI and is checked against DHS databases. FBI forwards any potential "matches" to ICE officers at the Law Enforcement Support Center who look at the person's record for past immigration violations and criminal history.

Several things could trigger a detainer for a non-citizen, and with the significant expansion of what constitutes an "aggravated felony"—a category of offenses that could make one deportable—it became even easier for officials to expel people from the country. The term "aggravated felony" originally referred to three crimes: murder, weapons trafficking, and drug trafficking. The 1996 Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigration Responsibility Act significantly expanded this definition by adding two long subsections that could be applied retroactively. This has created an ever-widening list of crimes that can be considered aggravated felonies, such as a theft offense with a sentence of a year or more—even if the sentence is suspended. Many aggravated felonies have been interpreted by federal courts to include misdemeanors, and many are nonviolent offenses, underscoring the sensationalistic nature of the term, which is construed to apply to non-citizens only, and often applied to those holding green cards.

Widening the enforcement and deportation web even further is the category of "crimes of moral turpitude"—which include charges of fraud, forgery, and controlled substance violations—and the stage was set for today's deportation regime. According to the Florence Immigrant and Refugee Rights Project, which has provided legal services to thousands of detained immigrants in Arizona, DHS charges many undocumented people with crimes under these categories, such as using false documents or minor drug offenses (even possessing a pipe), and this makes it very difficult to qualify for any form of relief or bond. The fundamental legal parameters defining who is a criminal are expanding. With the post-9/11 security bonanza came more resources than the lawmakers of the 1980s and 1990s could ever have imagined. There are now more people to deport than ever before.

Secure Communities is the shining star of this deportation machine. If ICE determines that a person is a "criminal" or "removable alien," this information is sent to one of the twenty-four field offices that ICE has in all major U.S. cities. The field office will then examine each case, and if it wants to expel someone and initiate the prerequisite removal proceeding, ICE will issue a detainer.

Tryon tells me that when detainers are issued, "jails will hold people for up to seventy-two hours for us." ICE officers will pick them up at the jail and transport them to where we are sitting in the Batavia facility.

With approximately 34,000 beds at their disposal nationwide, Tryon says, ICE has the budget and resources to expel 400,000 people from the country per year. He says this without emotion or embellishment. He says it as if the detention facility were a factory. According to National Public Radio, that's exactly what it is: Congress has given "U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement . . . a policy known as the "detention bed mandate." They must keep those 34,000 beds full each day.

Tryon doesn't mention that the United States has never before deported so many people.

Even so, the glass is half empty. There are most likely more than 11.5 million people in the United States who do not have the proper paperwork necessary to live and work here legally, Tryon tells me, "and you have to take your resources and go after the criminals. If we catch someone and find out that they are a farmer without correct papers," he says, "we will release them."

Batavia is located right between Rochester and Buffalo on Interstate 90. Although the ICE facility is huge, it is still easily missed and completely out of view from the throughway around this town known for horse racing and Batavia Downs. Unlike Manhattan's Chelsea office, the detention center here is clearly marked, one of the nine such facilities that ICE actually owns in the United States. The other 300 or so sites are contracted out, more than half to private prison companies and the rest to cities, towns, and counties.

Club Fed

Sometimes the Batavia Police Department calls ICE when officers pull over a person who speaks only Spanish. When ICE agents interpret, Tryon explains, they must ask, by virtue of the subject only speaking Spanish, if they have documentation to be in the country. But he insists that the ICE officers are also humanitarian. He insists that "if the Batavia police call us over because they have pulled over a Spanish-speaking woman who is nursing, we will let them go on their own recognizance."

This is Tryon's tone—a sort of jagged humanitarian benevolence—as he explains things to me during our tour of the innards of the detention-deportation apparatus. Yes, there are the coils and coils of razor wire. Yes, there are the motion sensors placed all around the detention center. Yes, there are the dark control rooms where guards look into dim monitors twenty-four hours a day, 365 days a year. And, yes, he would say, this is what is needed in the world to keep people like Tryon, me, and other law-abiding U.S. citizens safe.

There are also good things—such as taco night on Tuesdays. Everyone loves taco night. But even taco night has its drawbacks, because it's a fire hazard, Tryon explains. "That's when they put the tacos in the toaster." When we enter the industrial kitchen, Tryon exclaims with a broad smile that this is the "best-smelling place in the facility." It gets its food from Sysco, the same company that delivers food products to restaurants all over western New York. In other words, "delicious and nourishing," Tryon gushes.

True, he concedes, a few of the "bigger guys" sometimes complain. He explains that some people may think they need more than 3,200 calories, which is the "correct amount."

Tryon shows us the basketball court that also serves as a chapel and a mosque. He tells us that they even removed the Buffalo sports teams' logos that had been painted on the wall, because the incarcerated Muslims complained that the logos were inappropriate for a space being used for religious worship. Not only are the detainees' spiritual needs satisfied, so are their intellectual and artistic pursuits. There are two small libraries next to the basketball court, and one is a law library—much needed, since many of the detainees have no lawyer and only limited, if any, legal support.

And there is the "public art." We see this when we are walking down a hallway that extends—for what looks like a good mile—from the medical unit to the processing room, past the kitchen and laundry room to where the detainees are caged. In a section of the hallway there are dozens and dozens of flags of countries drawn in perfect rows on the wall by, Tryon tells us, done by a feisty Jamaican who had disciplinary problems but was an excellent artist. We stop there for a moment to appreciate the flags, as if Tryon were a restaurateur showing off the diverse international backgrounds of this Batavia resort's visitors. Tryon says that there have been people from every single one of these countries, his hand sweeping the landscape of colors and flags. I see red-striped Peru and Iceland and Honduras.

"Except for one," he says. "Can you guess which one?"

"The United States?"

"No."

"Canada?"

"No," his voice is restless with this one, Canada being so close.

"Iceland?"

"No, no, no."

"I'm giving you a hint," he says, "I am standing right in front of it." He is standing in front of North Korea.

In the processing room Tryon finally boasts, "They call it Club Fed." He pauses, then says: "Both the detainees and the staff." He continues to talk about how well the prisoners are treated. I am looking at a group of men, all wearing white ICE T-shirts, joking behind the counter. One of them stands out: he has a blond flattop and a red face that looks as if he had too much sun on the Fourth of July. I wonder if it is difficult or easy for these men to explain their jobs to people outside their world.

Indeed, what Tryon is describing with colorful and comfortable language is the Batavia facility as a perfect, micromanaged, "Border Patrolled" territory in which everything is under control and everyone is under surveillance, even in the shower. The person who designed their phone system, for example, should be "awarded a medal," Tryon says. He can listen in on phone calls, all of them, past and present. "Good intel," he says, tapping his head. It is a place where everyone is properly classified in red, orange, and blue uniforms according to their criminal records.

Despite all this, the only reason anyone is in the facility is that they are non-citizens who are in the United States without the proper paperwork, like a visa or green card. If they were U.S. citizens, they should not be there, although citizens have been detained and deported before, as will be discussed later. If they have committed a crime, and the majority have not, they would have already been released by the criminal justice system. This civil detention is considered administrative; its purpose is to hold detainees in place so they cannot skip out on their hearings. They are not here to be punished. "Detention centers are not legal punishment," said Jacqueline Stevens. "They are for people who are trying to pursue their civil right to remain in the country." The idea that that these detainees are "criminals" is a dangerous myth that even penetrates the halls of Congress.

But you would never know this when we visit Bravo One on the final leg of the Batavia tour. It is an area divided into three separate sections. We go up the stairs to a control room. It is like climbing up one of the Border Patrol's desert surveillance towers. Like the central control room, it is dark inside and has lots of switchboards. There is no need for monitors, since the large windows overlook the three areas. Through the window we are watching the "reds," the worst criminal offenders, finish their lunch. Though the number constantly fluctuates, says Tryon, on any given day there might be a 100 or so "reds" in detention. These are the "aggravated felons," Tryon explains, taken from the street. Although he uses this term that is specific to immigration law, and which could also be derived from a previous misdemeanor, he doesn't explain further.

One of the reds is a black man with short dreadlocks. He has on a blue medical mask and holds a spray can in his hand. He is wiping the tables and cleaning up after lunch. Another man who looks as though he may be of Asian ancestry is the only person who continues to eat. He is eating slowly. Maybe he doesn't want to go back to his cell where he is locked down for fifteen hours a day in administrative detention.

I ask Tryon again about the number of beds. He says the inmate population will go up "when harvesting season comes." When he says the word "harvesting" his voice cracks, and he pauses awkwardly. Earlier in the conversation he said that they didn't go after people who work on the farms. Then he says, "Sometimes Mexicans want to get picked up after harvesting season to get a free ride home."

Through the window we can see some of the "reds" returning to their rooms. We can't see the bunk beds from where we stand, but Tryon says that they are welded to the wall. Tryon explains that the men we see below us are "dangers to society," even though it is civil detention.

We turn around and look out another window. This time it's the "oranges." "Oranges" might have committed some minor crime in their past. They aren't completely in the clear, like the "blues," but they are not locked down, like the "reds." Most men are crowded downstairs, some sitting at white tables surrounded by blue chairs, some mingling around, only a few upstairs where there are no separate rooms. There is bunk bed after bunk bed after bunk bed. I can see an "orange" sleeping on one of the beds. He has on a white T-shirt and orange pants, and his arm hangs over the side.

"We have to make gut-wrenching decisions sometimes," Tryon says about the large number of removals ICE executes each year, "but I don't let my personal feelings get in the way." Tryon pauses, looking down at several men grouped around the phones, many attempting to make calls to loved ones. "I'm here to enforce the law. If they don't like the law, why don't they dialogue with Congress and change that law?" He continues talking as if the very presence of the men in front of him were a critique of his work.

"I have four children of my own," Tryon says. "It's gut-wrenching, but the law is the law."

Most of the detainees are people of color. The men employed to guard them sit behind a countertopped island in the middle of the detention area in a sea of orange jumpsuits.

People stay anywhere from two weeks to seven years, Tryon tells me. "These guys appeal, appeal, and appeal until they finally get tired of appealing and say they can't do it anymore. They hold the key to their own jail cell." They also hold the key to their permanent banishment from the United States.

However, Lauren Dasse, executive director of the Florence Immigrant and Refugee Rights Project says: "Many times, detained immigrants must make the extremely difficult choice of whether they stay in detention and fight their case, or take a deportation and be sent back to a country that in some cases doesn't feel like home, because they have been in the United States for so long, or they may have a fear of persecution if they are an asylum seeker. Both options include being separated from their loved ones." Dasse refers to something that Tryon doesn't mention: many of the people who Homeland Security detains are established in the United States and have families. Dasse explained to me that the vast majority of detained people are represented pro se—by themselves—in immigration court because neither they nor their families have the resources to hire an attorney. The Florence Project (which is located in Arizona), like many other organizations across the country, provides assistance to people who are forced to represent themselves in court.

"We have to act for the greater good," Tryon continues, "and take out the greater risk to society. It's been proven by John Hopkins or someone, I can't remember who," he says, waving his hand in the air in annoyance at his own inability to remember, "for every aggravated felon we take off the streets, five less crimes are committed in the country." When I search for the study Tryon wishes to cite, I can't find it.

"You do the math," he says, "400,000 times five." He pauses to allow us to attempt the complicated mathematical feat. With this, Tryon describes a ravenous monster that is kept in line with bureaucracy and budgets.

An article by Nina Bernstein in the New York Times quotes another term used by many for the massive growth in the number of people—non-citizens—being detained by the United States: "the immigration gold rush." Now towns from New Mexico to New Jersey, from the Pacific Northwest to the Deep South, are in hot pursuit of these prisons and jobs, and the rivers of federal money gushing into them.

The Times article describes a detention center in Central Falls, Rhode Island, one of many town and city governments with an ICE contract to set aside jail "beds" for people being detained due to their residency status. In cash-starved Central Falls, where the prison is located just beyond a Little League baseball field, the federal government paid $101.76 per day for each bed, a bit lower than the national average of $122 per day. This "rare growth industry" (during the recession, the Times stresses) has helped private companies such as Corrections Corporation of America (CCA), whose contracts with the Department of Homeland Security have more than doubled. In 2005, Corrections Corporation of America made $95 million. By 2011, it was making $208 million per year. Its stock prices have risen right along with it, as has its lobbying budget. Since 2003, CCA has spent on average $1.8 million per year to lobby Washington officials. They want detainees, more and more detainees.

Since the 1980s, jails have been a good "investment," with new strict laws that led to the mass incarceration of drug offenders. The immigration "payoff came after 9/11 in an accelerating stream of new detainees: foreigners swept up by the nation's rising furor over illegal immigrants," according to Bernstein's article in the Times.

Like Central Falls, western New York is a place where incarceration rates help boost a struggling economy. The Batavia ICE facility, Tryon says, is one of the biggest job providers in the region. He says this knowing that Buffalo, the second-poorest city of its size in the United States, is a place starving for good jobs.

"There are 270 contracted employees at work 24/7, including a medical unit, guards, and health services. The guards," he says, "make $30 an hour."

"They make more than me!" Tryon exclaims, with a controlled law enforcement smile. "They're not gonna get another one like that around here." Besides keeping the world safer, his smile seemed to say that immigration detention creates jobs, and even makes careers.

Border Patrol Court

Every single weekday in the Tucson Federal Courthouse, dozens of people face a judge as a result of their residency status. Pérez Méndez is among those dozens. While he insists that he is twenty-one years old, he has the soft facial features of a child of fourteen or younger, which makes the interaction between him and U.S. magistrate judge Jacqueline Marshall even more painful to watch. Pérez Méndez's crime occurred four days before, when he crossed the U.S.-Mexico border without authorization. The U.S. Border Patrol arrested him in the Arizona desert. And now he is in the courthouse—shackled at the wrists and ankles, and chained around his waist—along with sixty other people convicted for "illegal entry" into the United States.

The judge has singled Pérez Méndez out, and unlike the others, who approach her in groups of five, this kid, obviously frightened, is the last one to shuffle up to the stand. He does it alone.

"I don't believe you are twenty-one," says the judge. "We don't lie in this court. That isn't how we proceed." She explains that this is why she singled him out.

Pérez Méndez doesn't respond.

"Do you have any relatives? Parents? Brothers? Cousins traveling with you?"

"No," he says. The judge looks at him suspiciously, trying to discover, I imagine, the motivation for his assumed lie.

The judge tells him that she has no other choice but to place him under oath. She explains to him what that means—if he were to lie, then it would be perjury. Perjury is a criminal offense carrying prison time. "Is that what you want?"

Up to this point the Operation Streamline proceedings—a zero-tolerance border enforcement program that criminally charges all people who cross the U.S.-Mexico border without authorization (not through an official port-of-entry)—have unfolded as they normally do. On this day in mid-March 2012, fifty-eight men and two women, all with brown skin reddened after days of walking under the blazing Arizona sun, have already approached the judge in groups of five with their heads bowed submissively, their bodies weighed down by metal shackles and chains. In Tucson alone, approximately 17,850 people will approach the judge this way in 2012. Some will go to prison, and everyone will be formally deported, all for being in the United States without the proper papers. They are wearing clothing dirtied and damaged by the desert. They contrast sharply with the much whiter judicial personnel, well dressed in pressed shirts, dress pants, and polished shoes, some milling about or checking their smartphones, others sitting at tables.

Programs like Operation Streamline, which is active every weekday in more and more places along the southern U.S. border, are a significant part of the U.S. Border Patrol's interior advance, and its 2012-2016 goal is explicitly stated in the title of the strategy paper "The Mission: Protect America." Operation Streamline has been in existence since 2005, running in the Tucson sector since 2008, and now is a cornerstone program of the "Consequence Delivery System" of the Border Patrol's strategic plan. In many targeted areas along the border, undocumented people from Mexico are no longer "voluntarily" returned after arrest, as part of what Border Patrol termed the "catch and release" protocol. Like the ever-hardening border, things have changed in the judicial apparatus. They now face a judge.

These types of multi-agency efforts (Streamline includes the U.S. magistrate, federal judiciary, U.S. Attorneys' Office, and the U.S. Marshals service among others) are paramount to the Border Patrol's quest to efficiently enact the "layered approach to national security"—meaning more boundaries of all shapes, sizes, and purposes, well past the actual international divide.

U.S. Border Patrol chief Mike Fisher describes the strategy as a "multi-layered, risk-based approach" to "enhance the security of the border" by more efficiently using the resources and personnel at Border Patrol's disposal, particularly after the massive post-9/11 resource buildup.

"This layered approach," Fisher explains, "extends our zone of security outward, ensuring that our physical border is not the first or last line of defense, but one of many."

Operation Streamline joins ICE operations and programs such as Secure Communities in the execution of many more arrests, producing much more human fodder for the incarceration mill. All the men and women facing the judge on this day will be charged with the federal criminal charge of "illegal entry" since they were "caught in the act." The courtroom becomes the judicial extension of the U.S. international boundary line. And, as displayed so poignantly through Judge Marshall's interaction with Pérez Méndez, the judge becomes one of the many anointed border guards for a mushrooming judicial enforcement program. For example, the U.S. Senate's proposed immigration reform bill in June 2013 calls for an expansion of Operation Streamline in Tucson from 70 to 210 people prosecuted per day.

However, on another occasion, when a group of students asked Marshall about the effectiveness of Streamline, she responded by saying it was a waste of resources. When pressed by students from Vassar College as to why she even did it, she said she had to put her children through college. Magistrate Judge Bernardo P. Velasco continued Marshall's logic, telling a group of students that Operation Streamline is a "jobs bill" as recorded by student Elena Stein: "We have Border Patrol officers who are employed, prosecutors employed, marshals employed, courtroom deputies employed, prison guards employed. A lot of people are making good money to support their families."

In this context, it seems almost like absurd theater watching Pérez Méndez attempt to take the oath. He has to raise his right hand, but can barely do so because it is shackled and chained to his left hand. So he also has to raise his left hand almost up to his chin in order to be able to lift up his right hand too. This is sufficient for the judge, but incomplete, because his right hand is never entirely raised.

After the oath, the judge asks, "Do you want to consult your lawyer?"

His lawyer, referred to by the judge as "Washington," is a tall African American man who towers over Pérez Méndez. They talk for a few minutes off to the side.

Washington then approaches the stand again and tells the judge: "My client has maintained since the get-go that he is twenty-one years old. His birth certificate gives him a birthday in 1991."

"It could be fake," the judge says abruptly.

"Yes," Washington says reluctantly, "he has the mannerisms and look of a fourteen- or fifteen-year-old." It's true. Pérez Méndez looks younger than twenty-one. He looks like a teenager who should be starting high school, not shackled in front of a judge.

The judge looks at Pérez Méndez, who is now under oath.

"How old are you?" asks the judge.

The following pause is loud. To the right side of the judge sits the interpreter, who speaks her question into a microphone on his headset. Pérez Méndez's headset, with its curving band under his chin, almost looks like another fixture of the detainment apparatus that chains down his ears.

"Twenty-one years."

The judge looks up to the ceiling as if she were trying to see the sky.

"Where are you from?" she asks with a hint of exasperation.

"Chiapas."

"How far is Chiapas?"

"Three days."

"Did you walk?" the judge asks, but it is unclear if she means from the border or from Chiapas.

"Yes."

A bald, stocky man dressed in a fresh-pressed shirt and tie stands up and says: "I'm sorry, but the U.S. government does not believe that he is twenty-one years old."

The judge says that she both applauds and agrees with the U.S. government.

Then, surprisingly, she drops the charges against Pérez Méndez. But she isn't finished.

"Three days," Marshall says, dwelling on the number, "I imagine you came to find a job?"

The new question seems to startle Pérez Méndez. His story could be one of many. If he is under eighteen years of age, as the judge suspects, he might be trying to unite with other stateside family members who are also in the country without authorization.

"There aren't as many jobs as there used to be," Judge Marshall says. "Once you get back there," she says implying Chiapas, "don't come back."

"And those who hire illegal aliens are no longer going to do so," Marshall continues, adding, "they will be charged," as if the Department of Homeland Security were busting employers left and right throughout the country.

Perez Mendez stands there nodding to everything that she says, but the judge is just getting to her punch line: "If you do it again you will be charged. And do you know what will happen to a person who looks like you in prison?"

She pauses.

"They beat people who look like you in prison. That should scare you. Do you understand that?"

Pérez Méndez only nods.

I Have Got to Get Out of Here

After watching ICE take away his father in a white van, the normally talkative, yet extremely sensitive, twelve-year-old Adrián will not say another word for hours. He will not see his father, who will be incarcerated at the Corrections Corporation of America (CCA) facility in Eloy, Arizona, for another six months. Adrián's grades will plummet at school. His teacher will tell his mother, Luz, "His body is here, but his mind is not." He and his brother, Sammy, will be extremely aware of the police. Both of them will be sensitive to knocks on the door. Like many other children whose parents have been taken away by immigration authorities, any knocking will produce anxiety and they will try to hide their mother. Luz says that they tell her, "I don't want them to take you away."

They are not the only children left in the traumatic predicament of suddenly losing one or both of their parents. Between 2010 and 2012 this has happened 200,000 times. According to the Applied Research Center in its report "Shattered Families: The Perilous Intersection Between Immigration Enforcement and the Child Welfare System," there are so many obstacles between parents and their children that Child Protective Services has terminated parental rights in 5,100 of these cases.

When Gerardo and Luz came to the United States, Gerardo bought a fake Social Security card in order to be able to work. For eighteen years, Gerardo used this card to work for construction contractors and restaurants. He was first arrested in the Tucson restaurant where he had ascended from dishwasher to busboy to cook. Cooking, according to Luz, is Gerardo's passion. He has an excellent sazón, she says, an excellent chef's intuition, and the couple has dreamed of opening a restaurant together. Even in jail his chef's mind is always at work. He even learned how to make cheese from the cafeteria milk while in detention.

The first time the police came, he was chopping vegetables in the restaurant's kitchen. It was a joint police operation between the Tucson and Mesa Police Departments that arrived with a caravan of vehicles, both marked and unmarked, including several armored cars. The Social Security card he was using (and paying into) was that of a twenty-one-year-old from Phoenix. He spent five months at the Pima County jail. When he was released on bail, it was not his family but ICE that picked him up. He was charged with a crime of "moral turpitude"—being present without "lawful admission" to the country—and placed in removal proceedings. ICE transferred him to the CCA facility in Eloy. After several months there fighting his deportation, his family, with help from their community, posted bail. This was not identity theft. It was the equivalent of somebody getting busted with a fake ID.

He was out for a year when ICE arrived with the intensity of Navy SEALS going after Osama Bin Laden. Homeland Security had decided that letting Gerardo out on bail was a mistake. He was a "criminal alien" and should not be on the streets.

It was a cold and windy March day in southern Arizona when I traveled with Adrián and Sammy from Tucson to Eloy to see their dad. The latest news was that there was actually a white guy in there, a French guy. "The first one I've seen," Gerardo told the kids before we left.

Gerardo has been in the CCA facility in Eloy for one year. The kids have been going every two weeks for the last six months. They know the routine. They know we have to wait in the foyer with all the other families, most of whom only speak Spanish. They know that in the real waiting room there is a vending machine. It only sells junk food and candy, but getting some is a goal that the kids latch on to. I am here because the family has offered to give me a glimpse into their nightmare. When they finally allow us into the waiting room, Adrián and Sammy beeline it to the vending machine. Then they poke each other with pens for a bit and start playing I Spy. I walk to a plaque on the wall that shows a list of CCA's employees of the month. Then I watch a shift change. The guards come in carrying clear backpacks, their law enforcement belts over their shoulders.

To economically depressed Eloy and the surrounding area in central Arizona, the four CCA prisons have not only created jobs as the top employer, but also helped the small city of about 17,000 inhabitants upgrade its water lines and purchase new police cars as well as fund the construction of a "new town playground." This is quite an improvement for a town that looks almost abandoned when you drive past it on Interstate 10 between Tucson and Phoenix, and where 32 percent of residents still live below the poverty line. CCA also pays Pinal County $2 per bed per night, which funds the county's now infamous sheriff's department.

When they announce Gerardo's name we all jump to attention. The two children run to their dad. There he is, standing in a dark green jumpsuit, the equivalent of an "orange" in Todd Tryon's world. They hug him at his waist, one kid on each side. Gerardo tenderly caresses their heads and faces. I look on awkwardly, not saying anything. I shake Gerardo's hand. His face is friendly but worn. His dark hair is parted on the side. We greet each other in Spanish.

In the visiting room emotional reunions are going on all around us. To my left a woman and a man sit across from each other, their hands clasped across the table. The woman wears a dark green jumpsuit like Gerardo's. They don't seem to be talking, this couple, just staring into each other's eyes. I watch them for a full fifteen seconds before the man whispers something across the table as if quietly fighting the clicking seconds.

Across from me, the two children place themselves on either side of their father. Gerardo tells Adrián to work harder at school because he's now failing five of his six classes. Gerardo's voice has a sad tone to it, as if he knows why Adrián hasn't been putting in the effort. Sammy places his chin on Gerardo's shoulder on the other side. The thick-eyebrowed Sammy is the quiet one, and he seems to be content with just Gerardo's physical presence.

From across the table Gerardo tells me about a job that he had hauling material to build a swimming pool. He hauled really heavy stuff, so much that when he got home he collapsed. "I was so exhausted," Gerardo says, "that I even said no to the kids when they asked if they could massage my back."

"I just don't want my kids to have to do the same thing," he tells me. He looks from side to side, from Adrián to Sammy, curled up on either arm. Gerardo then looks to Sammy. He asks about school, his life. He asks them both about Luz, their mother. Since he's been here they lost their apartment. Now they are living in someone else's house, a member of the community who offered them space in her home until they got through the crisis.

"I have got to get out of here," Gerardo says with a release of emotion. He says this knowing that he has to remain strong. He could leave if he signs the "voluntary" removal papers, as he almost did when his mother died. He almost did it. He came close. But he didn't.

"I have got to get out of here," he says once more, as if talking for the 400,000 people ICE will arrest and detain that year. It is such a large number, yet its horror is concealed and bureaucratized. It only reaches the national dialogue for brief moments before the next news item drowns it out. Gerardo seems to realize the futility of trying to stay in Arizona with family—you can hear it in his tone of voice.

Michelle Alexander, author of The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, closely captures the experience of Gerardo and so many others incarcerated in this deportation machine in a speech: "All of this, all of these systems of racial and social control, and this entire system of mass incarceration all rest on one core belief. And it is the same belief that's the same Jim Crow. It's the belief that some of us, some of us, are not worthy of genuine care, compassion, and concern. And when we effectively challenge that core belief, this whole system begins to fall right down the hill."

In Eloy, as Gerardo continues to look longingly at his children, the gray-haired guard behind the desk, who seems friendly, loudly announces that visitors only have five minutes left.