Books are becoming obsolete. Publishers are croaking. Newspapers are going belly-up.

Paper's going away. Boo. Hoo. Hoo.

Really, who'll miss it? Before anybody here falls into a hyper-literate bibliophilic frenzy, let me assure you that I say this as a devotee of the written word: Hell is where there's nothing to read.

As a child, I'd read my dad's college texts at the breakfast table, not because I was smart or curious, but because they were what happened to be near the Wheaties. In fourth-grade, I read books about the lives of all the presidents' wives in the school library. Once, stuck out in a trailer in the desert with nothing else, I read every word in a 4-year-old New Yorker, including the agate-type entertainment listings in the front. Etc.

I should also clarify that I'd be upset if I weren't confident that the production and dissemination of highly organized language will be an even bigger business in the future than it is now. At present, things are a bit in disarray due to rapid technological change, but the economics will get fixed. So I'm certain that the Niagara of words that I like pouring through my head will still be available. Language, I need. But paper? Not so much.

Paper was, of course, a seminal invention. I recently learned that the technique for making it was carried from China to the West, along with other revolutionary ideas and technologies, by Genghis Khan and his descendants. In fact, their period is known as the Late Middle Ages, because the innovations—and disease vector—they brought with them kick-started the Renaissance. (You want to talk about rapid, disorienting change coming at you like a screaming warrior on horseback? Check out the 13th and 14th centuries.)

I found this out, by the way, from one of the best books I've listened to in a long time: Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World, by Jack Weatherford. Highly recommended.

No paper was involved in my enjoyment of the astounding history of the Mongol horde, nor in my perusal of the scores of other books I've gulped down via iPod since my friend Maura Grogan turned me on to Audible.com. That's not to mention the hundreds of free podcasts that have helped keep my left brain happy while I walk the dog or clean the house or drift off to sleep.

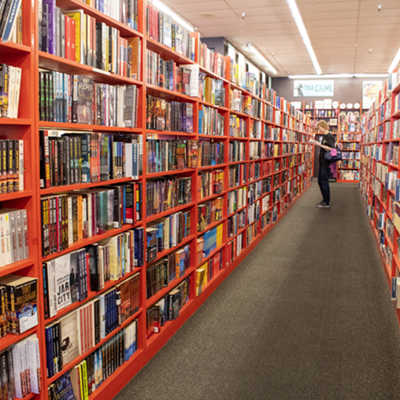

I still like printed stuff fine, and for many purposes, it's handy. But it also perpetually threatens to overrun my house. And, excuse me? Schlepping books to Bookmans is annoying, because they never want all of them, so then the orphans have to be schlepped to the Friends of the Pima County Public Library Book Barn on Country Club Road, where I abandon them against the wall, because, really? I'm supposed to figure out which four hours a day they're open?

On a more adult note, I simply can't see it as a bad thing that we'll be chopping down fewer trees to supply the disposable surface for Twilight novels, and classifieds, and Target ads. And is it ultimately sad that we'll be using less diesel to haul paper around? Or that fewer paperbacks printed in China will be hauled literally halfway around the world to market? No. It's tough on a lot of people in the short-term, but in the long run, it's a good thing.

As for the shakedown in the publishing industry—oh, well. It occurs to me that for decades, academic presses have been ripping off college libraries, and textbook publishers have been colluding to steal from college students and their families. A kid goes off to school, and the first thing that happens to him is that he's trapped into paying insane prices. For what? For books. Extorting a grand—or more—per year from every poor kid and his parents for textbooks is simply not the way to make friends for your industry or fans of your product. We reap what we sow, people.

So. I treasure a few books my grandparents and parents owned, because they belonged to them. And powerful memories reside in the books of my childhood and in those that my son loved. But it is memory and association that makes them beloved objects, not the fact that they're books. The essence of books is not their physical form; it's the words that live within them.

Paper isn't over, but it's fading. That's OK.