California always had more than its share of scandal and scoundrels. Leland Stanford used the governorship to become fabulously wealthy during the building of the Transcontinental Railroad, even jawboning Utah's Brigham Young into providing cheap Mormon labor for the final stretch of the project. Golden State politicians who followed Stanford would line their pockets with illegal schemes involving everything from avocados to water.

In late August 1934, however, the world turned upside down. With the state and nation deep in the grip of the Great Depression, the front-runner for governor wasn't another money-grubbing glad hander. Instead, the man who grabbed the public's attention that year was a pre-modern hippie who lived in a pink shack in Pasadena and went around preaching vegetarianism and other crackpot health schemes. He was a Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist and an inveterate pamphleteer. Charlie Chaplin was his best friend and among his enemies was a 6-year-old Shirley Temple.

Upton Sinclair, whose novel about the meat-packing industry, The Jungle, had so shocked the nation that the government was forced to create the Food and Drug Administration, decided to run for governor almost as a lark. He had always been on the fringes of politics, content to just throw verbal grenades over the walls. Indeed, when he ran in the Democratic primary, he was an admitted socialist--and never backed away from that label.

Sinclair won the primary in a landslide, and early polls showed him having a double-digit lead over incumbent Republican Governor Frank Merriam (whose campaign manager was a young Oakland attorney named Earl Warren). Sinclair was riding high on the EPIC (End Poverty In California) program, a mishmash of socialist rhetoric and rah-rah Americanism that the author had come up with. The EPIC word was spread by pamphlets that were sold in the streets for a nickel and helped fund Sinclair's grassroots campaign.

Sinclair's victory in the primary sent shock waves around the world. California's most powerful man, William Randolph Hearst, had spent the summer in Europe, traveling with his mistress, Marion Davies, and sucking up first to Benito Mussollini and then to Hitler. The day Sinclair won, Hearst was in Munich, trying to get an audience with Hitler. Hearst saw Sinclair as a threat and vowed to derail the writer's campaign.

Perhaps even more concerned than Hearst were the heads of the major motion-picture studios in Hollywood, who somehow convinced themselves that if Sinclair won, he would socialize the studios and make them organs of the state.

The studios began deducting one day's pay from every employee--from production head down to janitor--to fund the anti-Sinclair fight. (They glibly called it the "Merriam Tax.") In all of Hollywood, only one person--James Cagney--stood up to the studio heads. He said that if they took one day's worth of his check, he'd give the rest to Sinclair and openly campaign for him as well. The studios backed off.

While Hearst's papers churned out anti-Sinclair editorials, the Chandler family's Los Angeles Times took a different tack. They paid two investigators to pore over every word that Sinclair had ever written, and each day, in the upper corner of the front page, they ran a quote--taken out of context from a novel or a play or a letter to a friend--with an attribution to Sinclair.

The studios jumped in with what many consider to be the forerunner of the attack political commercial: They began churning out fake newsreels and forcing theater owners to run them. The most famous used several out-of-work actors dressed as hobos arriving in California via rail. The "reporter" goes up to one and asks why he has come to the state. "Why, when Upton Sinclair wins the governorship, he'll turn California into a socialists' paradise, and I won't have to work."

Several people who worked on the newsreels went on to form a PR firm that would help get Ronald Reagan elected some 30 years later.

Just about everybody in the country chose sides. H.L. Mencken, one of Sinclair's best friends, nevertheless railed against the EPIC campaign and its leader. Will Rogers, who always tried to poke fun at both sides, was openly friendly toward Sinclair, while the movie studios trotted out Shirley Temple to speak against him. Richard Nixon, who had just graduated from Whittier College, wanted to join the Merriam campaign, but accepted a scholarship to Duke Law School instead.

As the media giants chipped away at Sinclair's lead, a third candidate entered the race. Raymond Haight (for whose family the Haight-Ashbury section of San Francisco is named, and the son of a former governor) joined the race as a moderate. It would prove to be the difference. On Election Day, Merriam beat Sinclair by 200,000 votes, while Haight drew 300,000 votes for himself.

The EPIC campaign faded into history, but many of the people who had been drawn into the political battle would go on to nudge California to the left. Upton Sinclair remained in California for another 30 years but left the state when Ronald Reagan was elected governor.

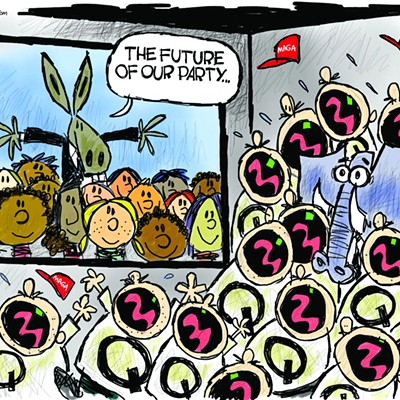

So when you tell me that California has a barn burner of a governor's race involving a front-runner who apparently only recently discovered that he's Hispanic, a movie star son of a Nazi, a former commissioner of baseball, a porn star, a smut publisher, a former child TV star, the worst stand-up comedian of all time, one of Bill Walton's sons and about 200 other people, the response is, "Yeah, and?"