It broke my heart when Barry quit the band. It broke all of our hearts. So we recruited my gifted younger brother Stuart to take Barry's place on guitar and keys. By then we were doing bigger shows, dates with Culture Club and New Order among others, and we moved to Los Angeles.

In L.A. we lived with our girlfriends/wives/roadies in a single rehearsal space—well, a cavernous concrete room—twelve of us on the fifth floor of the old Pabst Blue Ribbon brewery near Chinatown. That entire floor of the brewery had rooms rigged into rehearsal spaces, which were mostly rented by wretched glam-metal bands. It'd become a warfare of cacophony when more than one band would go it at once. Sometimes five or six would be bashing away, all day and into the night. There was but a single bathroom with a leaky shower for not only all of us, but the entire floor. We had our crew, our girlfriends, and my wife. We had no money, no cars, except those belonging to girlfriends, and I'd sometimes bum quarters from metalheads for quarts of Colt 45. It was summertime, humid, and we breathed truck and car exhaust from the nearby freeways. We were bone-thin hungry.

We strung up blankets and clothes for privacy, which made that ugly room into an even uglier shantytown, a rock 'n' roll third world. No foul odor went undetected, no sexual tryst unheard, no unpleasantness unfelt. We created little "bedrooms" of found objects, and mine was constructed of boxes filled with unsold Gentlemen Afterdark albums. For light there was a single bulb that dangled from the ceiling, maybe twenty feet up. You'd have to climb a ladder at night to turn it off and pray you wouldn't tumble down in the darkness. Our gear was set up in our room too, and we'd rehearse sometimes, but we never accomplished much. Cross's girlfriend found work at a nearby bakery and would haul home 45-gallon garbage bags stuffed with day-old croissants. She saved us because often that was our only food. Sometimes when the pickings became too slim we'd be so hungry we'd battle slithery roaches for the moldy, bottom-of-the-bag croissants.

There was a barrio across the street, and behind us to the west were acres of industrial wasteland connected by spines of railroad tracks. The downtown skyline at night was rare beauty, which we could see out the backdoor and on the fire escape. The city lights and the cool air filled me an indefinable yearning that'd haunt me all night, reassuring me that I was in this place because I could tolerate it more than any other place.

Nelson was also living in L.A. and was also working for Pee-wee Herman, and sometimes he'd pick me up and we'd go housesit Pee-wee's place while he was out of town. That was real refuge away from the brewery. And I'd drink every last Coors Pee Wee had stashed in his refrigerator. Pee Wee would come home and bitch that someone drank all his beer. A few us made coin trimming Pee Wee's hedges and mowing his lawn.

We did many shows in L.A., a few at this chichi Beverly Hills club called Chez Moi—a sort of leftover disco for the jeweled set who were too afraid of Hollywood. We'd play and folks like Diana Ross would show up and shake their heads and complain that we were way too loud. Some of us would arrive in Cross's girlfriend's car, which had been victim of a hit and run out in front of the brewery and the rear end was completely smashed in and the trunk no longer existed. It had a top speed of 40 mph and looked like a giant injured snail as it moved slightly sideways down the freeway. It's a wonder the thing was still drivable. At Chez Moi the only way to park was valet. And, for whatever reason, the only way we could start the smashed-up Datsun was with a screwdriver. We'd pull up in this battered beast to this five-star venue on Rodeo Drive and crawl out like kohl-eyed street urchins. We'd hand the valet the screwdriver and somebody would scrounge up a quarter tip.

But jocularity was fleeting. One day the Summer Olympics came on the tiny black-and-white TV that we had. I made the mistake of watching the men's cycling road race. I saw that my old cycling teammate, Alexi Grewal, was in the race. I'd lived with him in Aspen, Colorado and at the U.S. Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs and had traveled the country with him racing road bikes. He was older than me, but I used to beat him. But I'd quit racing to play in a punk band in Tucson. That day, on that little black-and-white TV, I watched my old teammate win the Olympic gold medal. I was stunned into emotional paralysis, dumb with regret and sadness, and I pitifully thought of myself as a bike-racing has-been at 16 and rock 'n' roll has-been at 21. I got up and bummed coins until I had enough for two quarts of Colt 45 malt liquor. I stepped out into the afternoon sun—it was one of those hot and hazy-dirty L.A. days—and walked to nearest liquor store. Gave shape to my worldview.

* * * *

A year later the band was done and my wife Stefania had left me. I was broken. I moved back to Los Angeles with Doug Hopkins (future Gin Blossoms) to start a band, which didn't work, and we drank in a Hollywood motel the whole time. We had an investor who had no money, another third-rate hustler who was fresh out of jail and wearing an Andy Warhol toupee. I returned to New York with Stuart. It was a fool's errand because we trusted the word of yet another con who said he owned a big 48-track studio where we could live and record for free, but he really tended bar, owned a portable cassette four-track recorder and lived in an old house on Stanton Island that was almost unlivable because it was being rehabbed. It was unbelievable.

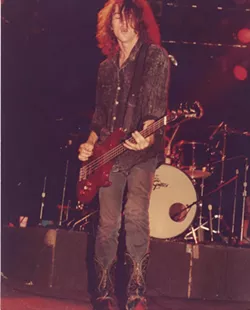

Johnson had gone off to front a band called Undertow, and that didn't last. I was back in Phoenix sleeping on people's couches, spending hangover days reading at the library, and counting nickels for beer. I DJ'd and played acoustic sets at clubs. A big payday came in the form of Gentlemen Afterdark "reunion" shows, which brought the band together again. We rediscovered the magic and reformed minus Fred Cross but with bassist Kevin Pate, and we wrote and recorded in earnestness. Spinal Tap began to feel like prophesy as the revolving door continued. At one point Watson moved to Los Angeles and recorded with Giant Sand and others and we had Phoenix drummer Rich Contadino in the group until Watson returned. But things were a mess; we went through a number of managers, we weren't talking with each other, and there was no money. Then Watson split for good, joined Color Code, a band signed to Island Records.

We enlisted drummer Jon Norwood, which was a turning point. This lineup became the best version of the group because Stuart, Robin and I had developed, as writers, producers and performers, and Norwood and Pate together happened to be one of the best rhythm sections the state had ever produced. I'd also remarried. Things were looking up.

We all moved back to Los Angeles and played every venue and shithole, and did good support slots on big shows and landed a great manager in this guy Wayne Sharp. But Guns N' Roses were huge then and Hollywood was alight in the dismal glitter of these fake glam bands, and then there was us, lost in the morass, and Pate's heroin habit was out of control. There was no cultural context for what we were doing music-wise either, but we played at clubs like Scream, Cathouse, the Coconut Teaszer, The Roxy and The Country Club with these bad bands. We were perpetual outsiders, and we only had ourselves, but people were taken aback when we'd play. They'd never seen anything like us.

We met with hit producer and label suit Jimmy Ienner, who been following our band and calling us frequently. Ienner, as a producer, essentially made the Raspberries in the '70s, and that's why I loved him. He did lots of stuff, produced Grand Funk Railroad and The Chambers Brothers and The Bay City Rollers, and he was responsible for the 1987 soundtrack to Dirty Dancing, which sold more than 35 million copies and was one of the biggest-selling albums ever. One night Johnson and I had a meeting with him at his suite at the Beverly-Wilshire Hotel. We drank a dozen of his Heinekens and ate all his shrimp while he explained that he was going to take care of us. He'd been telling us that our songs like "I Go" and "Stories" were to be massive, "like U2 massive." Said we had "brains, looks, heart and hooks." He told us that we had nine hit songs and just needed one more to make a perfect 10 for an album. An album of hits. That way, he said, all the major labels will be bidding. We trusted him. But he kept saying that the tenth song that we needed was eluding us, and we'd write, record and send him more. He'd say the same thing.

Looking back we should've been releasing our songs on an indie label, a record every two years, an idea guys like Ienner scoffed at. Through the decade we'd turned down the offers from the indies. We thought going the small-label route was a waste because no one would ever hear your music if it's on an indie. Just how wrong could a band be? We recorded enough songs in good studios to fill a number of albums. But we were half-deluded, wanting to be rock stars. We didn't consider how that kind of thinking was reductive and killed creativity.

One day in 1989, we were recording in A&M studios in Hollywood. We got a demo deal with the label and we spent a lot of time getting the songs right, spending two weeks on just three songs. This kickass-haired knob-twirler named Rob Jacobs was producing; a guy who by then had worked with U2 and a handful of other name artists. He was the real deal. He'd badmouth labels and suits, and do everything his way in the studio. U2 respected that in him. They wound up using his mixes on such hit songs as "Angel of Harlem."

On our final mix day, then-label head Jimmy Iovine came down and listened to some final mixes. Now Iovine and guys like him made us nervous. To us they had the keys. We were at their mercy and I resented them for it. Iovine was already a mogul, a guy who came up a musical iconoclast, securing his status as a star-making music-biz legend after having worked closely with John Lennon, Bruce Springsteen, Tom Petty, U2, Patti Smith, and so on (he'd soon partner up with Dr. Dre, and he's now one of the chief architects of Apple Music). So we had to respect him. At least pretend to. He stepped into the studio's control room, nodded to Jacobs, who then fired up the tape machine. Iovine positioned himself between the speakers and listened to two songs, "Promises" and "Holiday," bouncing his head, pumping his leg and closing his eyes as he listened. When the songs ended we all looked over at him, and he waited a moment to say anything. Then he grinned, looked at each of us, and said, "These are incredible songs. They're hits. Don't play these for anyone else." As he turned to leave, he said, "Get ready, gentlemen." And then he walked out. Jacobs turned to us, and said, "See? I told you. You guys are in."

We were stoked. After the starvation and living on couches, the myriad hours of shows, rehearsals, failures, hopes, lies and drinking, we were finally in, based on what this legend was telling us. I floated on air for weeks. Then our manager said that Iovine had gone to Europe. Then he said that Iovine had stopped returning his calls. A few months later Iovine launched Interscope Records, focusing on hip-hop and urban dance music.

Around that time we appeared on national TV, a telethon of some sort broadcast from Disneyland. It was at night and we did a four-camera live-performance lip-sync to a several of our songs. We played on big colorful stage in front a chirpy canned crowd and some Disney characters. Mickey Mouse was there dancing and frolicking along to us, his big heads swaying from side to side, and so was Ludwig Von Drake, Donald Duck and Goofy. Disneyland was closed that night and it felt eerie and lonely, all innocence gone. Before we played I went and downed a pint of brandy next to the "It's a Small World" ride in Fantasyland. I was thinking about how it had all come to down to Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck. But my parents saw the show in Tucson and were very proud. That counted.

This was art versus commerce, and we were growing up and beginning to understand just how easy it was to be on the losing side of things. Had you showed us a foot we would've showed you any number of ways to blow it to pieces. Heroin had many times abducted Johnson and Pate. My choice was always booze and coke. I did "important" record label showcases so hammered that I needed to hold on to the mic stand to keep from tumbling off stage. I used to tell myself that I was lucky and smart that I'd chosen alcohol, because it was legal and didn't involve needles. I really used to think that.

After the go-nowhere A&M demos, our momentum waned, and we returned to Tucson, back where we started, in 1990. Norwood and Pate stayed behind in L.A. We rounded up Phoenix bass player Paul "PC" Cardone and Tucson's Spyder Rhodes on drums, but the lineup never played a show. I got my first real job, making yoyos for company owned by Howe Gelb's dad. I wouldn't stop drinking, but my wife, Shireen Liane, had sobered up so we split up. She went on to make a great album on Virgin Records with her band The Slingbacks. I moved back to Phoenix and started a band called the Beat Angels with Norwood and Pate, released two albums and toured, and began writing and editing for a living, and got sober. But all of that's a whole other tangled, beautiful and ugly trajectory.

The life was hard on people. The world can be a random bag of shit and heartbreak, and when its centered on a core group of people it can wind up feeling tragic. Count the ghosts; they head in either direction. Our soundman Nino Notaro and bass player Kevin Pate are both now dead because their livers had surrendered. Our second drummer Jon Norwood died young of cancer. One of our other soundmen, Jon Suskin, OD'd on heroin. Original bass player Fred Cross drank like no one I'd ever seen, and after his Gentlemen Afterdark stint, he joined Caterwaul, and then disappeared down a dark road. Our early and longtime manager Brian "Renfield" Nelson committed suicide several years ago.

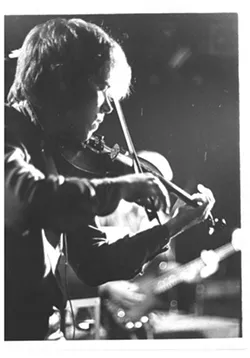

Of other Gentlemen Afterdark guys, Watson wound up in Bob Dylan's band for a number of years and played with lots of folks including Alice Cooper and Warren Zevon, and is now in the soon-to-be giant Tucson band XIXA. Johnson had myriad hurdles and played with everyone from David Slutes and the Sand Rubies to Greyhound Soul, and he now lives in Los Angeles and is an accomplished singer/songwriter. Stuart lives in the U.K., released an album and singles on the Creation label with his band Super J Lounge, and then he started his own company called Thundering Jacks where his inventive arena video designs have earned clients in everyone from Peter Gabriel and Kings of Leon to 50 Cent and Coldplay. Barry plays his violin for a living in Northern Arizona.

It was all just around the corner for us, but everything just slowed down like weekday hangovers. And that show with Billy Preston at the Santa Monica Civic all those years ago? We didn't get booed off the stage at all. We cancelled at the last possible moment. Of course.

Get a free Gentlemen Afterdark song from their A&M demos.

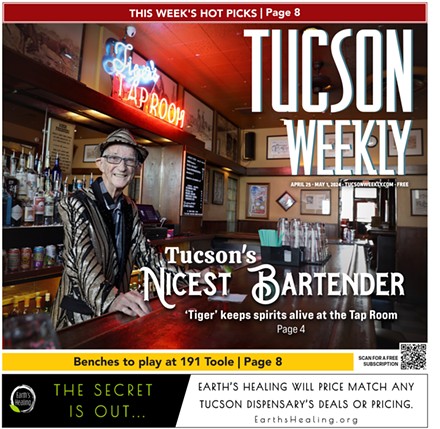

Smith and his fellow Gentlemen Afterdark will be reuniting at Club Congress' 30th anniversary celebration during HoCo Fest on Saturday, Sept. 5.