Friday, April 5, 2019

Inclusion Matters

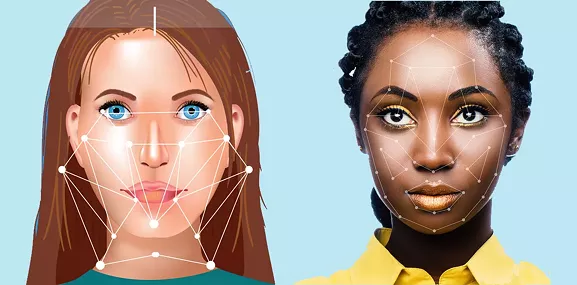

It's the early 1990s. Imagine a U.S. high-tech company has made a quantum leap in face recognition software. The product is so far ahead of the competition, it corners the market and becomes the industry standard.

In this imaginary scenario, the company is owned and staffed by African American techies.

What are the chances the weakest link in the software would be its inability to recognize dark-skinned faces? Almost zero, right?

When early incarnations of the software were tried out on the company staff, any problems with differentiating and recognizing people with dark skin would jump out at them immediately. The company would make it a priority to pinpoint and correct the problems, because who wants to create a program where they, their coworkers, their mothers, fathers, boyfriends, girlfriends, wives, husbands, sons and daughters can be mistaken for someone else? The recognition system for dark-skinned faces would be as close to flawless as the company could make it.

Of course, before bringing the product to market, the company would make sure the system worked with lighter skinned faces as well, because that's where the money is. Still, its accuracy might drop a bit because Anglos were excluded from the initial testing and tweaking process, and they weren't in the room prodding their fellow techies to work out the bugs.

But if, instead of it being an all-African American company, a quarter of the top people were Anglo, white faces would have gotten more attention from the beginning. If you add Asians and people from other ethnic groups into the mix — and women, let's not forget about women — you're likely to have as close to an equal opportunity face recognition product as any company could create.

Now let's jump back into the real world. One of the weakest links in today's face recognition software is recognizing darker faces. In a grotesque example, in 2015 when Google users asked to see images of gorillas, some African American faces were likely to be included. Google apologized and promised to fix the problem. Instead of fine-tuning the software though, Google simply blocked gorillas from its image search options to take care of that one specific problem.

An article in Thursday's Star is about Amazon's face recognition software which appears to have trouble detecting African American women's faces. As you might imagine, the problem wasn't discovered in house. It was pointed out by a female, African American researcher at MIT.

Both Google and Amazon tried to make excuses for their errors. A Google spokesperson said its software made mistakes with other people's faces as well. Amazon attacked the methodology the MIT researcher used in her recent study, though a group of Artificial Intelligence scholars defended her work. Both companies thought it was perfectly fine to downplay the problem and minimize the effort they put into finding solutions.

Problems like these arise regularly in the private and the public sector because too few members of minority groups are sitting at the table. If Silicon Valley had more African Americans in positions of power, they could throw a spotlight on racially insensitive aspects of the corporation's work, which are invisible or unimportant to others, and work to find solutions to the problems.

Here's another recent example, or two or three, from Hollywood.

Almost by accident, Hollywood has discovered a new way to make money which has been hiding in plain sight for years. They've begun to give African American directors big-budget projects and let them feature black actors in their films. As a rule, directors of color have struggled to get a green light for their movie projects, except for the occasional small film geared to art-house audiences.

Seemingly out of nowhere, two African American directors have earned critical acclaim and huge numbers at the box office. There's writer/director Ryan Coogler with his films Fruitvale Station, Creed and the blockbuster sensation Black Panther. Following almost immediately is writer/director Jordan Peele, who created his out-of-nowhere hit, Get Out, followed by his latest feature, Us. The directors and the actors they used in their films have received overdue recognition because they had a chance to show what they could do in front of the worldwide audiences who have flocked to see the films.

Here's a related story that's less well known. Peele wanted to find an African American composer to score Get Out, but there weren't many options in Hollywood's databases. So Peele scoured music on Youtube and found Michael Abels, a 56-year-old composer who has written symphonic works and had some of his music included in short films. (Arizona angle: Abels was born in Phoenix.) The resulting score for Get Out is so original, vibrant and eery, it's almost a character in itself. Peele used Abels again to score Us. Because Peele had the directorial authority to find talent on his own, the movie industry has "discovered" Abels. He's scoring an upcoming film for Netflix.

If there were no Jordan Peele who was determined to find an African American composer to score his film, Abels would still be laboring in relative obscurity.

This kind of bias stemming from a lack of diversity in positions of power runs rampant at all levels of our society, the result of historical inequality and prejudice. And let's not forget to add the problem of benign laziness. It's easier to do what you've always done and keep putting the same old faces in positions of power than it is to reach out and try something different.

Lately, things appear to be opening up a bit on the inclusion front, or so it seems to this white guy who shares racial blinders with other Anglos. But even if I'm right and the country is becoming more inclusive, it's only a small start. We have a long, long way to go.

Tags: Face recognition software , Google , Amazon , Ryan Coogler , Jordan Peele , Michael Abels , Image