Jones was director of Tucson's Center for Creative Photography then, and eminent photographers routinely dropped by the family home in West University. But on this occasion, Callahan noticed an unfamiliar print pinned to the kitchen wall.

It was photo of a white paper bag on the sunny patio out back, the scored lines of the concrete fanning out below it in a criss-cross pattern. Like Callahan's best work, the picture was an elegant abstraction of lines and light and shadow. And it was Murray's.

"Who does that belong to?" Callahan demanded. "That's very good."

Callahan was one of the masters of 20th-century photography, and his words meant everything to her, Murray says.

"It was truly the first validation I had."

Since then, Murray has gotten plenty more. Critics have been mesmerized by her audacious nudes--of children, women and men--by her shimmering still lifes, by her riveting self-portraits. Located somewhere between ordinary time and dream time, her silvery black-and-white photos suggest elusive psychodramas. As the critic Joanna Frueh, a sometime Murray model, has written, her simple shapes, bathed in light, conjure up the "everyday magic of existence."

At the age of 40, 10 years into her career, the backyard-trained photographer won an NEA grant. The next year, she followed up with a U.S.-Japan Exchange Program fellowship that paid for her to live and work for six months in Tokyo.

Locally, Etherton Gallery has given her three shows since she first took a Rollei camera in hand in 1977. In honor of her 60th birthday this year, the gallery right now is staging her fourth exhibition, the one-woman Psychologue, a 30-year retrospective of her work.

Seventy-four of her glistening photos, painstakingly printed in her basement darkroom, hang on the walls of the downtown gallery. In all his years in the business, proprietor Terry Etherton says, he's never given any other artist such a large show.

"Seventy-four is a lot," he says, "more than usual. We were talking about her turning 60, and doing a show of maybe 60 images, calling it '60 by 60.'"

But when Murray brought in the 74 gelatin silver prints, Etherton couldn't bear to exclude any of them. He came in alone on a Sunday afternoon to figure out how to hang them.

"Magic happened," he says. Motifs emerged. Circles, angles, eyes, limbs, breasts practically arranged themselves.

"Her work falls into four categories: self-portrait, portrait, nudes and still lifes. And she handles these categories seamlessly. The nudes are bathed in the same light as the still lifes. Her use of natural light is amazing. It's all bounced and controlled. No one else quite does anything like that."

Etherton has published a catalog of some 42 of the works, complete with an essay by Frueh.

"We wanted to do something that would last outside the show," he says.

The printer added silver to the inks to give them Murray's characteristic gleam, and the glittering monograph, shipped out around the country, is attracting attention.

Not bad for a self-taught photographer who didn't graduate from high school or college, let alone art school, who didn't start photographing until the age of 30, and who began her life in America in a struggling immigrant Irish family.

Frances Murray's living room feels like one of her still lifes. The palette is limited, even austere. The walls are pale ivory, the chairs a subdued earth green. And everywhere vases and bowls and balls and candlesticks in silver and glass glisten in the morning light.

Her teapot is white, and her teacups, of Irish Waterford china, are rimmed with silver.

"I love my tea," she says, pouring milk from a creamer that's a silver sphere. "I have it every morning."

Blessed with crystal blue eyes and snowy hair, Murray also loves the shimmering objects that surround her. Many of them make their way into her photos.

"It's the magpie in me," she says. "Magpies fly up high and search for shiny things. I've been collecting for years, glass and mercury objects."

She doesn't always know quite how she'll use each twinkly piece.

"In time it gets revealed. I realize, 'That would be a great prop for this particular still life.'"

Murray insists on natural light for all her photos, whether they're taken in the house, in the yard or in her studio shed out back.

"I'm fascinated by objects and light, or the possibility of light."

When she started photographing seriously, she borrowed a camera from Jones and took a quickie course from David Burckhalter at the Tucson Museum of Art. Her first subjects were her twin daughters, Star and Rebecca, her own face, her back yard, the desert light beaming through the windows.

"I stayed close to home," she says. "I brought things into my circle, my psyche. I had no interest in going out. I photographed my children, our pets, still lifes. That was my universe."

She would pose her daughters, naked as the day they were born, against mysterious shapes and shadows, or incorporate the kids' toys into surreal narratives.

One day in 1983, she scattered glitter on her daughter Star, then about 11, and had the child cover her eyes with spoons. Star put on an old hat drawn from the kids' costume box, and its metallic beads mirrored the sheen of the silverware.

"I use a few carefully selected objects," Murray says. "Otherwise it's too forced." Without the spoons, the resulting photo, "Dream Cards: Silver Spoons (Star)," "would have been a pretty picture." With them, it turns ambiguous.

"A question is posed, but you're not given the answer right away. Things are not necessarily what they appear."

One of her best-known pictures, "Self-Portrait/Black Hat: Nose" from 1983, pairs a shiny mirror with Murray's own face. It filled the entire cover of the Tucson Weekly back on March 9, 1988, accompanying a story written by none other than Barbara Kingsolver, then a regular contributor. Murray affects a retro look, wearing a vintage hat and a sparkly 1940s necklace, and the picture plays with illusion: the mirror doubles her own profile.

"These images bolt a viewer's eye to the wall," Kingsolver wrote. "They arrest, they suggest, and they startle. One does not walk away from them unmoved."

If Murray has stayed close to home in her photographs, among the familiar and the much-loved, perhaps it's because in her life she's moved, and moved again.

Tea-loving Frances Ellen Murray was born in tea-loving Ireland in 1947. By the age of 8, she had lived in Ireland, Canada and the U.S., and at 15, a family tragedy propelled her back to Ireland. At 19, she returned alone to America.

The immigrant themes of loneliness and loss infuse her photographs. None of them is set in an identifiable place. Landscape has given way to dreamscape.

"Many of my self-portraits have a sense of displacement," she says. "There are haunting reverberations. It's probably how I processed those feelings. Wasn't I lucky to have photography to do that?"

She started life in Drogheda, an industrial port town on the River Boyne, a half-hour north of Dublin. Her father, Thomas, was a carpenter who'd studied art at a technical high school and turned down a scholarship to art school in Paris, Murray says, because his family was too poor. Her mother, Jane McCormick Murray, stayed home with the children.

"My parents immigrated when I was 5 or 6," Murray says. "It had been a dream more of my mother's, I think. There was a lot of immigration then, people going to England, America. There was a recession in Ireland. Before we left Ireland, my father built a beautiful house with his own hands. There's a sadness to that. They probably used the money from the house to emigrate."

The family--mother, father, Cormac, Jean, "Frankie," Margaret and Desmond--sailed for Montreal, then traveled by train to Winnipeg, where Murray remembers the snow and the "bitter cold." (A sixth child, Patrick, would be born in Rochester, New York.)

Many Irish went to Canada first in those years, with a goal of getting ultimately to the States, and two years later, the clan succeeded in moving to Rochester. Though it was only marginally warmer than the Canadian west, Tom Murray had managed to get a carpentry job there, and the family bought a small house.

America's old revulsion for Irish immigrants had mostly disappeared by then, and the nation had not been seized with its current anti-immigrant fury. Still, Murray was acutely conscious of her otherness.

"I remember how painful it was. Kids were mean to us over our Irish accents. I was incredibly shy. I felt so isolated, so outside the norm."

There wasn't much money to go around, Murray says, but "Our house was the house where all the kids wanted to be. There was always something happening. The kids wanted to hear my father tell stories. He was a storyteller" who spun wondrous fairy tales of Ireland.

Her father's yarns triggered a lifelong love of narrative in his daughter, and many of her photos, she says, hint at stories. In the film-noirish "Dream Cards: Window (Becky)," from 1982, for instance, a little girl stares up at the camera, a tilted rectangle of light behind her head breaking through the shadows.

"It's like a still life from a film," Murray says. "It makes you wonder: What has happened? What is about to happen?"

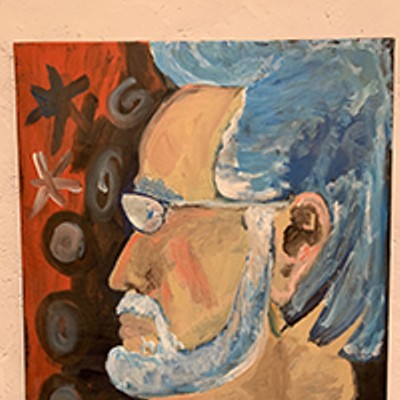

And despite all the kids and his daytime job, Tom Murray also pursued his art. He'd go off by day with his lunch pail to pound nails, but by night he'd be in his basement studio.

"He could draw and paint. He was extremely creative," his daughter says.

She has some of his work hanging in her house today: a lovely watercolor of King Lear, a nostalgic view of an Irish country lane ("I think my father was homesick"), an art-deco black-and-white woodcut of spiraling plants.

But for all Murray's closeness to her father, and her admiration for his artistry--not to mention her residence in Rochester, home of Kodak and the George Eastman House, the noted photography museum--she never thought of making a life in art.

"I was interested in art, but it never seemed like a goal. Coming from an immigrant family, you're trying to survive, thinking where the money was coming from. I didn't allow myself to dream."

The Murrays' American dream ended abruptly, when Tom Murray died a painful death from pancreatic cancer in 1962 at the age of 47. By the next summer, the family was on a boat back to Ireland. Her father's passing, Murray says, "fragmented our family."

The oldest, Desmond, stayed behind in the U.S., and the others were "parceled out" in Ireland. Frances and Jean went to a Great-Aunt Cissy, and their mother and three younger siblings camped for a time with another aunt.

Murray once again felt "misplaced." To the Irish, she was a Yank. Even her American Catholicism was found wanting by the strict nuns at her new convent school. But her academic career was about to come to an end. At 16, instead of finishing high school, she was sent with Jean to secretarial school in Dublin, with a view toward making her way in the world.

"It was a way to grow up very fast," she says, "to face some of the harsher realities of life." And after a year of learning shorthand and typing, she went out to work, at a solicitors' office, at an import-export business. But she missed America.

"I never settled in Dublin. I longed to go back to Rochester." So at 19, she did go back, alone. But Rochester was no longer home: "My family wasn't there. My father wasn't there."

Desmond was in Vietnam (where he would be seriously wounded). Her old friends were off at college, with none of her responsibilities, and Murray had to work, this time as a secretary at a travel agency. Then one day, when she was 21, she went out to sit on the front porch and her life changed again.

Harold Jones happened to stroll by. A young curator at the Eastman House in Rochester, he was on his way to a party on her block. He stopped to talk to the chestnut-haired young woman, and persuaded her to go to the party with him. They've been together ever since.

Meeting up with Jones not only helped Murray create a new family of her own, it introduced her to the fine art of photography.

"I had no idea about photography being an art form," Murray insists. "I only knew about tiny little pictures in family photo albums."

And she has the snaps to prove it. In a box at home, she keeps miniature albums from her family's Winnipeg days. Ansel Adams might have been making tour-de-force photographs of American landscapes then and Harry Callahan shooting his abstracted blades of grass in the snow. But to the uninitiated Murray, photography meant teensy pictures of her and sisters lined up in furry hooded parkas, or of baby Cormac in a snowsuit that made him nearly as wide as he was tall.

Her marriage to Jones in 1970 was the beginning of Murray's accidental master class in art photography. Jones had an MFA in photography from the University of New Mexico, and a job in one of the best photography museums in the country. And in 1971, when the twins were just months old, Jones was recruited to run the now-legendary LIGHT Gallery in New York City, the first gallery dedicated solely to photography.

The family drove to the Big Apple, the babies in the back seat, and moved into a flat in Chelsea before the neighborhood was cool.

"I was looking at photography in the gallery, and meeting photographers," Murray says. "It began to seep into my psyche. I didn't study photography--it was all going in and I didn't know if it would come out. I'd take the occasional snapshot."

Five years later, when Jones was offered the directorship of the UA's Center for Creative Photography, Murray went for total immersion. The Center's collection of the eminences of 20th-century photography provided her with the best possible teachers.

"I was looking at Emmet Gowin, André Kertész, Harry Callahan, Frederick Sommer, Linda Connor," she says. "It really doesn't get better than that."

Her husband, she says, was "extremely encouraging. I credit him as a mentor."

Murray was often at home with their little girls, feeling "an acute sense of isolation as I set up house again."

This time, though, the isolation fueled her new art, and her blossoming interest in photography became a game the kids delighted in. They loved playing dress-up, putting on costumes for their mother's camera, and then shedding those same clothes. Their mother began making nude images of her girls' perfect young bodies.

Having been raised Catholic and taught by nuns, she found the nude work intimidating at first.

"The children seemed very natural, but I realized I wanted to do (adult) female nudes. It was incredibly hard with my Irish Catholicism. Your own children you've seen ever since you gave birth to them. It's another thing to ask an adult."

Finally, conquering both her religious training and her own shyness, she asked a friend to model.

Soon Murray was making gorgeous nudes, simplified and bathed in light, their shapes cutting across the photo plane with what Frueh calls an "elegant edge."

"I celebrate the sensuousness of the human body," Murray says. But the pictures are never exploitive. They're "erotic in a surreal way," with an "ethereal eroticism."

Murray often combines her two loves, still life and the nude. One of her more arresting images, "Lumière," from 1990, pictures a slight, almost androgynous woman. Her head is draped in a shiny cloth that flies up and out beyond her. Or Murray will add a weird object--like the flower stuck to a woman's bare belly in "Female Still Life: Flower Pressing (Japan)," 1989--to surrealistic effect.

A whole series singles out body parts, treating them as still life. "Female Still Life: Limbs," 1983, emphasizes the "gorgeous roundness" of the buttocks, and the angular slash of an arm and leg.

Once Murray was comfortable photographing naked women, she moved into the dicier terrain of the male nude by making pictures of couples. "Intimacy/Isolation: Caress," 1987, is a rhythmic image, all white curves against black, of a man and woman holding their bodies together.

"I had the dynamics of the man and woman undressing in front of me," she says of the challenge. "It was a huge leap." But she took it. "The feelings of awkwardness took a back seat. The artist/director in me took front and center."

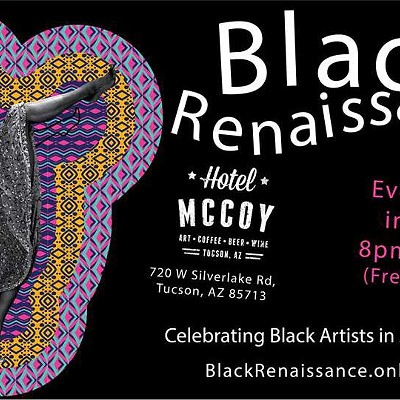

Murray has now lived in Tucson longer than any other place in her peripatetic life. Thirty years in, at the opening of her retrospective in September, Murray was not only surrounded by three decades of work made in the Old Pueblo, but by the friends and family she's cultivated here.

Her grown daughters (one of them pregnant) flew in from Portland, their husbands and a granddaughter in tow. Four out of her five siblings turned up, her sister Jean all the way from Ireland.

"Having the retrospective was a great honor," she says, not only to herself but to her late parents. "I have such tremendous awe and respect for my parents, what they endured for their family. All my life, I've been striving to have milestones to make them proud of me."

After giving up photography for a few years, Murray got herself back into the studio two years ago. She's still attached to film, she says, with no plans to go digital, and the retrospective includes several 2007 prints straight out of the darkroom.

One of them is "Self-Portrait: New Growth," 2007. It pictures Frances herself, with a thick plant atop her head. Like the fertile plant in her father's woodcut, it has stems and leaves joyously pushing up and out, on their way into unexplored territory.