Errol Morris' first documentary was 1978's Gates of Heaven, which focused on pet cemeteries. At the time, the great director Werner Herzog commented to Morris that because the subject was so un-cinematic, he would eat his shoe if the documentary was completed and shown in a public theater.

Two years later, the short film Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe was released.

In the decades since, Morris has tackled everything from Stephen Hawking's landmark book A Brief History of Time to hairless-mole experts to Vietnam War architect Robert McNamara. Somewhere in between, his 1988 documentary, A Thin Blue Line, helped overturn the conviction of a death-row inmate in Texas.

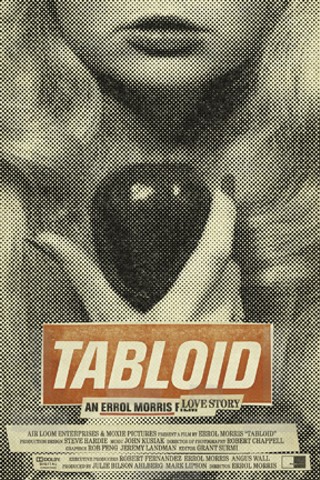

If there is a constant in his work, save for the Hawking documentary, it is that Errol Morris tells stories that are just laying there, waiting for someone to pick them up. His latest, Tabloid, connects some pretty weird dots to draw an even weirder picture.

In the mid-1970s, Joyce McKinney fell in love with and was set to marry Kirk Anderson. It would seem like a perfectly fitting relationship for the decade of Love, American Style, if not for two things: Kirk Anderson was a Mormon about to serve a mission overseas, and Joyce McKinney was an adult model. When Anderson "vanished," in McKinney's words, she tracked his missionary work to England and spared no expense to find him, hiring bodyguards and a pilot for a trip overseas to bring him back.

Once McKinney and her entourage arrived in England, the story broke off into two versions of the truth: It's he said, she said. She said Anderson came with her willingly, and they made sweet love for days and days in a country cottage, emerging just long enough to drive back into London to get married. He said he was forcibly abducted, chained to a bed and repeatedly raped, finally escaping her clutches when they drove back into London. It became known as the "Manacled Mormon" case, and McKinney became the subject of a very public trial.

Owing to how little things have changed since then, McKinney's tabloid infamy—multiplied exponentially in the gossip-addicted United Kingdom—made her a celebrity, and she showed up at film premieres and partied with the biggest British stars of the day. While we may not see Casey Anthony popping up at Sundance next year, it is worth noting that Amy Fisher was just featured on Celebrity Rehab; she's a "celebrity" by virtue of the fact that she shot the wife of her much-older lover.

As a filmmaker, Morris is not concerned about judging whether or not McKinney's rise to short-lived notoriety was justified. He merely presents the tawdry evidence. And as he nearly always does, he presents it beautifully. He relies on archival footage and studio interviews, and his unique bit of magic is combining his skill as an interviewer with his feel for editing. He calls upon McKinney, her pilot, and a writer for Daily Express, one of the British rags covering the salacious story, and peppers their commentaries with photos and news footage from the 1970s.

But Joyce McKinney's story is not yet complete. Even though she fell out of the spotlight in the early 1980s, when there was no 24-hour cycle to keep such oddities afloat, McKinney's name did pop up again several years ago. You can Google that if you want to, but it's more rewarding to see the equally bizarre and completely unrelated story in the way Morris presents it.

Many documentary filmmakers in the Michael Moore-inspired generation want to be instruments of change, and there is certainly nothing wrong with that. Sometimes, they emerge as Morgan Spurlock, kind of an absurdist who investigates more-serious topics as a guinea pig. Moore himself has been onscreen since Roger and Me, and while it's certainly effective for him, it does put a big dent in any supposed objectivity that documentarians are supposed to have.

Errol Morris, while certainly passionate about his subjects, is more of an observer. Moore interjects himself into each story he tells, while Morris is always behind the camera. It's not about the man making the movie, in other words. That may seem like a small point, but it allows him to go from films like The Fog of War and Standard Operating Procedure, two very sober indictments of the men playing chess with soldiers as American foreign policy, to something as odd and entertaining as Tabloid, with equal aptitude. And he makes better films than Michael Moore as a result.