Stories that go nowhere are generally not good entertainment. But stories about stories that go nowhere, as Joel and Ethan Coen have shown with A Serious Man, can be incredible.

The 14th feature from the Coen brothers, Serious Man starts with a message from the medieval Rabbi Shlomo Yitzhaki: Receive with simplicity everything that happens to you. Then, for the next 100 minutes or so, things happen that are impossible to receive with simplicity, because they appear, at least on the surface, to be complex, meaningful and deeply connected.

Or maybe they're just random events that coincidentally converge. After a brief folktale featuring a 14th-century shtetl, a rabbi and an ice pick, A Serious Man jumps forward to 1967, when the swirling psychedelia of Jefferson Airplane is trying to penetrate the suburbs of Minneapolis.

Professor Larry Gopnik (Michael Stuhlbarg) is having an ordinary day, trying to explain to a room full of physics students that they cannot simultaneously know the precise velocity and location of a subatomic particle. The world, as Heisenberg has informed us, simply doesn't work that way.

Meanwhile, Gopnik's son Danny (Aaron Wolff) is $20 short on the money he owes his pot dealer, Gopnik's brother is slowly going insane while siphoning pus out of an enormous cyst, and Gopnik's wife (Sari Lennick) is leaving him for a hairier, fatter, groovier man (Fred Melamed).

And so Gopnik begins, in the manner of a traditional Jewish story, a series of visits to increasingly renowned rabbis. He's looking for the figure in the carpet, the thread that will connect all the bizarre elements in his life.

But maybe it's the quest for patterns that's the problem. As though to provide a lesson for Gopnik, his brother Arthur (Richard Kind) is also looking for connections. He's developed a system for knowing everything, which he calls "the mentaculus," a kind of mental calculus. Only, when Gopnik looks inside Arthur's notebooks, he sees the convoluted diagrams and graphomaniacal scribblings of the mentally ill.

Is this what looking for answers leads to? It seems that the Coens are saying yes: The effort to know more than we can, to acquire knowledge of velocity and position, is a fool's task.

Or is it? Arthur starts winning large sums of money in poker, allegedly by using the mentaculus. After a student complains about a failing grade, Gopnik finds an envelope full of cash. Did the students leave it behind? The student's father, mimicking Schrodinger's cat, both affirms and denies that the money is a bribe for a better grade. And next door, a naked neighbor asks Gopnik if he takes advantage of "the new freedoms." Does this all add up?

While each event and element seems like a clue, it also seems as though they only come together for the mystic or the madman. The first rabbi (played brilliantly by Simon Helberg of The Big Bang Theory) urges Gopnik to find the beauty in a parking lot. A beautiful, beautiful parking lot. The second rabbi (George Wyner) tells him a shaggy dog story about the teeth of a goy. And the third rabbi (weirdly and wonderfully created by Alan Mandell) is mystically unavailable, having discovered what happens when the truth is found to be lies (hint: the joy within you does not survive).

I could go on to list plot points. They accrete like iron filings on a magnet, building up wave-like patterns until they just have to make sense. But the accretion may be the only sense they have.

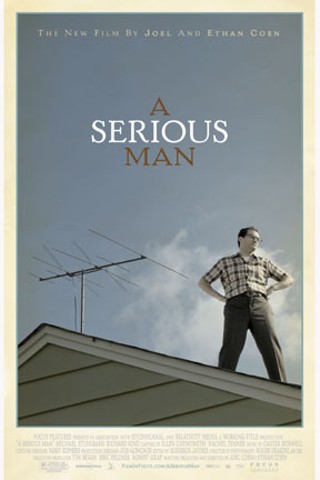

The Coens are aware of the mystery, and know how to use sound and silence, lighting and framing to bring this home. Jefferson Airplane's Surrealistic Pillow appears and reappears as though the lyrics will lead us to the resolution of the plot. The empty sound of treeless yards whistles to Gopnik as he stands on a rooftop and gawks at his neighbor's 1960s-style free-form bush. And every room, every face and every empty street has a bumpy realism that makes it feel dirty and true.

For the latter, cinematographer Roger Deakins is largely responsible. Deakins has been nominated for eight Academy Awards. He's also the greatest living cinematographer. And yet, he's never won the Oscar. I'm pretty sure Deakins won't win it for Serious Man, either, because his work here, though utterly brilliant, is sharply unbeautiful, and the Academy generally gives its award to whomever shoots the prettiest sunset and creamiest bosom-in-tight-bodice. But if there was any justice in the world, Deakins would not only get an Oscar for this film, but retroactive Oscars for virtually every other movie he's made.

The Coens are also immeasurably helped by their amazing cast of unknowns. Fred Melamed, as Gopnik's wife's lover, perfectly captures the sudden infusion of feelingness that infested America in the late '60s. Stuhlbarg is seamless in the lead, and Amy Landecker is simultaneously creepy, repellent and erotic as Mrs. Samsky, Gopnik's liberated neighbor.

But the fact that the cast is unknown, and that the film doesn't answer all its questions, might hurt it with the average American viewer, who generally prefers that his or her entertainment ends with Simon Cowell announcing a winner. The Coens have a much better ending for Serious Man. In fact, it's the best ending I've seen in years. So even if you have no interest in Heisenberg and mid-century American Judaism and Henry James and perfectly photographed lawns, come and check out Serious Man just for its final three minutes. They will metaphorically blow you away.