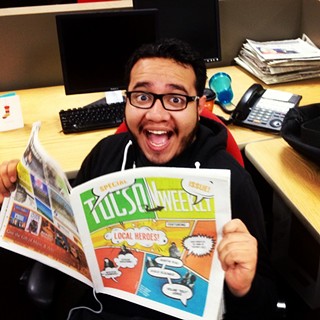

CESAR AGUIRRE

Sitting in the back of the Casa Maria soup kitchen in South Tucson, Cesar Aguirre discusses his work for the Catholic social justice organization and how he became a fighter for his daughters, their education and Tucson Unified School District schools.

Thinking back on the July cafecito he hosted at the John Valenzuela Youth Center, Aguirre reminds me that it wasn't the first time South Tucson residents had filled the center's large community room. But this time it was to give residents an opportunity to meet TUSD's new superintendent and to let him know they cared about their children's education.

"There was a lot of intention behind it," he says. "Here we were, getting a new superintendent and thinking about our struggles with the previous superintendent. We kind of wanted to open a door for a change in the culture of TUSD and be the first to reach out to him."

Most of the meeting was conducted in Spanish and new Superintendent H.T. Sanchez answered most of the questions in Spanish, too. Speaking in Spanish was also intentional, Aguirre says.

"One of the reasons we wanted to do it in Spanish was because I kept thinking about all the times I'd taken parents to TUSD board meetings and there was no translation, and parents walked out more confused than ever. We decided to flip that culture around and asked English-speakers if they needed headsets. For them, it was an eye-opening experience," Aguirre says.

Another goal for Aguirre was showing a united front to the new superintendent. However, to think that the room was filled only with parents and teachers representing South Tucson-area schools such as Ochoa, Mission and Pueblo would be wrong. Aguirre says more than 24 district schools were represented at that meeting.

Those alliances, which Aguirre says he remains committed to building, started late last year when the TUSD governing board held hearings on potential school closures. Aguirre had been working to keep open Ochoa, which his daughters attend. It was the second time the district had targeted Ochoa for closure.

Ochoa was taken off the closure list early in the hearings process. But rather than go home, thinking his work was done, Aguirre continued to show up at every hearing along with a large group of South Tucson parents and teachers to advocate for all of the area schools.

"Sure, when we started, it was about saving our schools and the education of our children in our barrio," he says. But during the hearings, "We heard many parents saying 'Don't close our school, shut down theirs.' There was a lot of negative energy between the different schools. I started realizing we were all facing the same problem. We were all fighting the same powers to keep our schools open and I couldn't understand why we were fighting each other to do that."

The focus on education is a no-brainer for Aguirre. The single father of two daughters in elementary school grew up on Tucson's southside. His parents were from Mexico. When he was 10, his parents, believing they were doing right by their children, moved the family out of the southside to rural Three Points. Aguirre says the transition was difficult for him. He was bullied in his new neighborhood and had a hard time making friends.

He eventually became involved in drugs and gangs. What helped him change, Aguirre says, was the birth and development of his oldest daughter. He had to do some time in the Pima County Jail, and when he got out his daughter barely recognized him.

"I got clean and started surrounding myself with different people," he says.

However, the mother of his daughters didn't want to get clean. She was still doing drugs when his second daughter was born. Aguirre, who had been sober for six months by then, spent this next three years fighting for custody of his children.

"It's hard, but I do my best," he says of being a single dad. "It's helped me change a lot of my ways of thinking."

Today, Aguirre and his daughters live at Casa Maria, where Aguirre now works. Besides working on education and immigration issues, he helps at the soup kitchen and with the Bus Riders Union, a community group dedicated to improving Tucson's transit system. "I've seen friends and family torn apart in this community through deportations. But I'd say now my idea of justice is broader and has helped me get involved in many issues facing our community. Now I'm doing what I love."

However, education issues and helping the parents of students realize that they have some control over how their children learn remain his passions.

"Public education is under attack and parents are the only group that can really make sure their children's education is protected," he says. "They have the power."

SYLVIA CAMPOY

If you think there's glory fighting for desegregation in the Tucson Unified School District, remember that TUSD's desegregation battle has been going on for nearly 40 years.

Sylvia Campoy has been officially part of the case since 2004, when she began her volunteer stint representing the Mendoza plaintiffs on behalf of Tucson's Latino students. The case goes back to the early 1970s, when a complaint was first filed by Roy and Josie Fisher on behalf of African-American students.

The district is now in the unitary status phase, meaning it must work within the confines of a legal agreement negotiated among all parties last year—TUSD, the Mendoza and Fisher plaintiffs, and the U.S. Department of Justice—by a desegregation expert appointed by U.S. District Judge David S. Bury.

That agreement is now in the implementation phase, which at times brings all parties back to court when there are disagreements over how to essentially change a district inside-out to better serve students. The areas in dispute have included special education, magnet schools, English-language learning, a curriculum to replace the beleaguered Mexican-American Studies department, and a multicultural curriculum.

Campoy may have been the perfect choice to represent the Mendoza plaintiffs. A TUSD governing board member from 1989 to 1992, a former TUSD special education teacher and former director of the city of Tucson's Equal Opportunity program, she knows the district well. She's aware of the discrimination and equality issues, and has remained steadfast in achieving justice for the plaintiffs, even in the midst of other political storms, such as the fight for Mexican American studies.

And she also brings personal experience with discrimination in TUSD to the negotiating table. When the sixth-generation Tucsonan started the first grade at Roskruge Elementary School in 1956, she spoke only Spanish.

"I wasn't just a non-English speaker, I didn't understand it and had no expressive or receptive English language skills," Campoy says.

Back then, kids with even moderate English skills were often held back in first grade, and sometimes they were sent to special education classrooms. Campoy's teacher took the approach that every time a student spoke Spanish out of turn, the student would be separated from other students. Campoy said she spent a lot of time banished to the steps of the school's massive staircase or to special education classes.

"Somehow they thought I'd learn English more quickly rubbing shoulders with mentally disabled kids," Campoy says.

She also received lessons about other misconceptions at an early age. Because Campoy was a skinny kid who didn't speak a word of English, her teacher thought she must be malnourished, so she was sent to the cafeteria to drink extra milk every day. "When I look back, that first year of school was very negative, but at the end I was doing fairly well for still not speaking (English) well. The teacher thought she was going to retain me, but my mother would not allow it. She advocated for me and I went on to second grade."

Despite the language barrier, Campoy says she made friends with other girls in her classroom.

"They took me by the hand and inadvertently taught me English," she says, tears welling up in her eyes. "I don't know why that makes me emotional. I suppose it's because it's an example of kids teaching kids, and another example of why integration of all kids is important—special education and English-language learners."

Positive or negative, those early years informed the person Campoy was to become—a speech pathologist and special education teacher, a discrimination and equality expert now working on the TUSD desegregation case.

"Maybe those years could have done a lot of damage. Maybe they did some, but we overcame the challenges by doing a lot of work at home. My mother made sure I got tutoring in English," she says.

This is the second time TUSD has gone through a post-unitary status plan process, and the second time for Campoy, too. Bury approved a post-unitary status plan in 2009, but in August 2011 the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals sent the case back to Bury and the district was forced to start all over again.

Now, as a representative of the Mendoza plaintiffs, Campoy talks to school groups and parents about the issues. She reminds district officials about what they agreed to do, and also works closely with the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Foundation, known as MALDEF.

"Everyone signed on the dotted line. It's important to remind the district that it can't dance away from what it agreed to do. That would be insanity for our children. We can't delay the implementation of the plan. That's delaying equality," Campoy says.

It isn't unusual for Campoy to hear from critics that the deseg plan wouldn't be needed if the district and parents just focused on improving struggling schools. "But that wasn't happening before. There remain inequality issues, some still in place going back to when my grandfather was in school," she says.

"Look, to rid an institution of institutional racism, the approach has to be systemic, otherwise permanent changes don't take place," Campoy says.

She's also had opportunities to give people outside the city a fuller picture of what's going on in Tucson, such as in June, when she was honored by the Plaza Community Services organization, headed by Gabriel Buelna, director of the documentary Outlawing Shakespeare. The award was presented to her by Chicano studies professor and author Rodolfo Acuña at a ceremony in Los Angeles.

"It was one of those full-circle moments," she says.

DUSTIN DIAL

Our hero's journey started when Robert and Marjorie Dial decided to uproot their family and move with their two boys from San Francisco to Tucson in 1979.

"I grew up in the '80s watching Super Friends and reading comic books. I grew up in the age of superheroes, where good was good and bad was bad," said Dustin Edington Dial, now a 37-year-old Tucson Police officer who regularly dons superhero garb to entertain ill children and raise money for charity. "There were no blurred lines. You had a definitive idea who the good guys were."

Dial can relate to the superheroes who were around before Frank Miller's Dark Knight Returns and Alan Moore and Dave Gibbon's Watchmen featured anti-heroes that changed the tone of superhero comics.

"I have a disdain for people hurting other people, and creating victims," Dial said.

Dial has been protecting and serving residents of the Old Pueblo for 14 years. The majority of his tenure has been in patrol beats, instructing at the police academy and in undercover work. He's currently assigned to the midtown beat. "My heart has always been in patrol," Dial said. "An officer exists, in my mind, to serve the public."

Last year, Dial was given the Tucson Police Association's Unsung Hero award for his fine policing and his countless hours of volunteer work. "I was very reluctant to take it," Dial said. "It's the biggest honor I have ever received. I was very humbled and I didn't feel right taking (the award) compared to the other nominees."

Before Dial started bringing his favorite childhood characters to life, he joined a monthly Star Wars fan club because he was bored. He was introduced to the 501st Legion Star Wars costuming group at the Bookmans Entertainment Exchange at North Campbell Avenue and East Grant Road. "They brought an extra storm trooper suit, they put me in it, and I was hooked," Dial said. "What got me was, one, being able to portray a character I grew up with and, two, the reaction from the fans was overwhelming. People were almost rear-ending each other on the street."

There are a couple of things Dial thinks about before constructing a suit from scratch. "I portray a hero I have always loved," he said. "And to portray a hero that everyone else recognizes, there's a monumental amount of satisfaction (when it) brings a smile to someone, especially a child.

"I never thought I could pull off wearing a superhero costume because I have struggled with weight issues my whole life," he said. But "I found a character I love and that lets me do it creatively, and that character is Doctor Fate." Doctor Fate has a full face mask that shield's Dial's double chin and the gold cape conceals his stocky build. Dial made all of the costume except for the boots and gloves. And he's started working out so he can dress up as Batman and Superman for Justice League Arizona, the charity he started.

"There was a Marvel costuming group, but no DC," Dial said. He created the nonprofit so that like-minded costume designers and comic book fans could bring smiles to faces young and old, and he set up a Facebook page to recruit members. The JLA makes regular appearances at the Diamond Children's Hospital and at annual events such as Relay for Life and Tucson Troop Support. The latter event is a party for families where the mom or dad is deployed overseas during the holidays. The JLA also attends the Phoenix Comicon convention to raise money for the Kids Need to Read foundation. "There are more JLA members in Phoenix than Tucson," Dial said.

Dial says he has spent more than $3,000 on crafting suits and building sets and props for the 501st Legion and the JLA. "I never consider it a loss because I enjoy it so much," he said. "My goal is to make sure that the league lives on beyond me."

Dial and his wife, Michele, have two children. Michele, who home-schools the kids, has started the Northwest Tucson Homeschoolers, a support group for families whose children are home-schooled.

The couple met in a Tucson AOL chat room. "We were the only ones in there that weren't 15 years old," Dial said. "We finally met and I scared her to death because I showed up wearing a biker jacket. I had to convince her I wasn't a biker, but a nerd."

ROLLAND LOOMIS

Rolland "Rolly" Loomis, a highway builder and concrete pipe manufacturer by trade, began dedicating his life to serving others around the world after making a deal with God 20 years ago.

"My mom, who was my best friend, became ill with melanoma. I told God that if he would save her, I would dedicate myself to doing his work. She was given six months to live but managed to live another 6 and a half years."

The extra time with his mother served as a call to action.

After moving to Tucson in August 2003, Loomis immersed himself in activities at St. Francis in the Foothills United Methodist Church, 4625 E. River Road. St. Francis works to promote equality and justice for the LGBTQ community, refugees, the homeless and other underserved populations.

When senior pastor David Wilkinson took notice of his dedication, he asked Loomis to serve as a lay pastor. Learning on the fly, he has served there for more than nine years, and for two years he's been the missionary for outreach ministries at the United Methodist Desert Southwest Conference. "In the past two years," Loomis says, "I've probably preached in 25 to 35 churches all over the country, and I have yet to find a church as amazing as St. Francis."

Loomis has also worked on projects in several African countries on behalf of St. Francis and the Desert Southwest Conference. He coordinated a multi-million-dollar fundraising campaign for a health-care initiative called Imagine No Malaria, a global effort that has helped bring about a huge decrease in the number of deaths from that disease. He has also been involved with the construction of schools and wells, organized mobile health clinics and developed curriculum for promoting LGBTQ equality.

Despite his local acceptance and strong support from many senior officials within the United Methodist church in the U.S., being openly gay has presented challenges in his path to becoming a fully ordained UMC pastor. "Don't Ask, Don't Tell is alive and well," Loomis explains.

As he fought poverty and disease in Africa, Loomis fought anti-gay discrimination there at the same time. Meeting and befriending the Rev. Dr. Eunice Iliya of Nigeria was a turning point in this struggle. When Loomis first came out to her, she "appeared shocked and didn't understand." When she told him she believed that no one in Nigeria was gay, he "reminded her that people in Nigeria pay the ultimate price if they are openly gay—the death penalty." Iliya is now considered a hero in the movement for LGBTQ rights in Africa, taking a stand within the church for equality. Loomis believes it's because of their friendship. "Barriers and misconceptions fall away when people have face-to-face conversations."

To help bring about a new era of acceptance for the LGBTQ community within the United Methodist Church, Loomis has recently been appointed to a part-time position working for the Reconciling Ministries Network, a group of pro-equality UMC churches in the United States. This job focuses specifically on having conversations and developing relationships with African churches on behalf of LGBTQ acceptance. He hopes that "in 20 years, being openly gay in this church will be a nonissue" both in the U.S. and in Africa.

Loomis was married to his partner of 32 years, Roy DeBise, in Binghamton, N.Y., last July 6 by ordained UMC pastor Steve Heiss, who has since been brought up on charges within the church for conducting same-gender weddings. Dozens of ordained pastors in the UMC are now following Heiss' example in what is being referred to as a "heating up" of the church. It is hoped that change will come about by overwhelming the system in a manner similar to the sit-ins of the 1960s civil rights movement.

When asked to describe the essence of his work, Loomis says he is "called to shine light in dark places." He believes "it's in our interest as a global community to take action to become a more peaceful, peaceable world ... and do the work that needs to be done to administer to all people."

We are fortunate to have Loomis shining his light in Tucson as he selflessly helps others and paves the way for justice and equality throughout the world.

GIULIO SCALINGER

As downtown Tucson changes rapidly, a few things remain the same. Take for instance, The Screening Room, at 127 E. Congress St. For almost 25 years the small theater has been a host to local films, film festivals and concerts.

Meet the man behind the curtain.

Giulio Scalinger got a taste for film exhibition while attending the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa, in the turbulent mid-1960s. The self-described “community rabble-rouser” for independent film, along with a few friends, created a film society at the school.

“This was a time when art cinema kind of grew out of universities, mainly English departments. They loved to do the comparison between the novel and film,” Scalinger says. “This was the time when filmmakers like Francois Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard were around. Our film society would show these films, which you wouldn’t see in any theaters. We were a rebel film society.”

Scalinger moved to London to attend film school. “It was the normal migration for a lot of South African liberals who didn’t fit in,” Scalinger says. After London, he moved to Ohio for a brief stint at another film school, and later ended up in Salt Lake City. But a film professor he had met in Ohio was teaching at the University of Arizona. When the professor invited Scalinger to run film workshops at the UA, Scalinger jumped at the chance.

“When I came down to Tucson, I fell in love with the area … the weather is exactly the same as South Africa,” Scalinger says. “I had started a media arts center in Ohio. Arizona didn’t have anything like that. So the plan was to bring me down here and to start a media arts center within the university. That fell through, but through all the research we had done that showed there was a need for something like that here, the Arizona Media Arts Center was set up as a nonprofit in 1985.”

Scalinger has been the director of AZMAC since then. Before The Screening Room opened in 1989, Scalinger presented unique film programming wherever he could, including the YWCA and the old Gallagher Theater on the UA campus. Then everything changed at the dawn of the 1990s.

“1990 was the birth of the Arts District, which I think was the renaissance of downtown. In 1989 there was a city agency who controlled this space and the places next door,” Scalinger says. “This space became available, and it was offered to us. We moved in here in September 1989 and we opened the doors in November. It was a space to give local filmmakers a place to show films.”

1990 also saw the birth of the Arizona International Film Festival, a celebration of films from around the world that runs every April. After a rocky start due to building code violations, the festival reconvened in 1993. A few years later, the festival went statewide.

“In 1995, the centennial of film, we took the festival all over the state, including Sedona. They liked it so much it gave birth to the Sedona Film Festival, a very successful festival,” Scalinger says. “We get a lot of questions like, ‘Why aren’t you the Tucson Film Festival?’ When we started, we said (our role was to represent) the state. We planted a lot of seeds in a lot of places. That’s what the Arizona Media Arts mission is all about.”

Other festivals, including Out in the Desert and the All Souls International film festivals, were first presented at The Screening Room. “If we offer the facility to an organization, then they bring their constituents. That’s what kept us going in the second phase,” Scalinger says.

Scalinger believes The Screening Room’s “third phase” is looming, tied to the much-anticipated arrival of the modern streetcar. Along with the streetcar, Scalinger hopes the new living spaces downtown will shape it into a brand-new community.

“I see us doing more and more to make us different. It depends on what the downtown community is going to be,” Scalinger says. “We always said collaboration is our middle name.

“People ask me to explain The Screening Room and I say it isn’t an art house, it’s a media community space, because that’s what it is.”