Except, as it turns out, September 11. I did not want to write about it, but Michael Parnell, the editor of The Weekly, asked nicely.

I agree that the day must be marked, but it's hard.

I have to say right off that I suffered no personal loss. The few New Yorkers I know well weren't anywhere near the World Trade Center and I wasn't acquainted with anyone on the planes.

My son, however, was in New York City. He'd moved there in late August to start his freshman year at Manhattan School of Music, which is up by Columbia, north of Central Park. He called that morning almost as soon as we'd heard the surreal, unbelievable news--but not before my brother had called to find out whether Dave could be anywhere near the Towers. I'd told him no, that Dave was miles away. I was sure, and I was right. He called almost as soon as I set the phone down--he's a really good kid--so I didn't have to worry.

He called from the roof of his dorm, the tallest building around, while he watched the smoke. He complained that classes were canceled, and that his first meeting with his viola teacher, who'd been in Europe for weeks, would be delayed even more. He'd heard already that the bridges were closed, and a rumor that another plane had hit the Justice Department. I told him it was the Pentagon, as far as I knew.

We got off the phone so I could start making calls to my brother, Dave's father, his grandmothers, etc., relaying the news he was OK. Then I got dressed and went to work. Of course, nobody got any actual work done that Tuesday. Personally, I didn't get much of anything done for six months.

Dave told us later that he stayed on the roof until he saw the second tower collapse. Then he went down to his room, ate, practiced and read until early afternoon, when, as he said later, "I started to realize what I'd seen." Then he walked 80 blocks south to see if he could find an old friend from University High who lived a block from the WTC. As it happened, he ran into Chris right away, on the sidewalk near NYU. He, too, was unhurt, although he didn't get back into his dorm for a month.

Shock and grief take a different course through every heart. In the days and weeks after the attack, some friends said that at first they were focused on the buildings themselves, and that it took them a day or two to get their minds around the fact that people were in there. The people on the top floors preoccupied me, however, from the first glimpse on TV. I think it was because of the jet that fell from the sky.

On October 26, 1978, two young women--sisters in a Chevy Vega looking for a place to park--burned to death when an A-7 out of Davis-Monthan dropped onto North Highland Avenue just south of Sixth Street, next to Mansfeld Junior High. The jet's engines had failed, we learned later, and the pilot had waited to the last second to eject. Coming in from the north, he made it over the UA, and was aiming for the big, empty athletic field that used to be where the Student Rec Center is now. He almost succeeded.

A jet without power drops like a rock with wings. It was just about noon on a lovely fall day, and I remember coming out of the Student Union and finding everyone stopped, looking toward the Science Library, which the A-7 had just barely cleared. Then came the enormous thud--not really a boom --and the column of black smoke. It had been in the back of my head all these years--the idea of the girls in the car and the jet fuel burning hot enough to ignite the asphalt on Highland.

The first thing I did after the crash was call my parents in Phoenix--I didn't want them to panic when they heard that two students had been incinerated next to campus. A zillion things happen over the years, but the bad ones stay with you, so they seem to repeat. That's my theory.

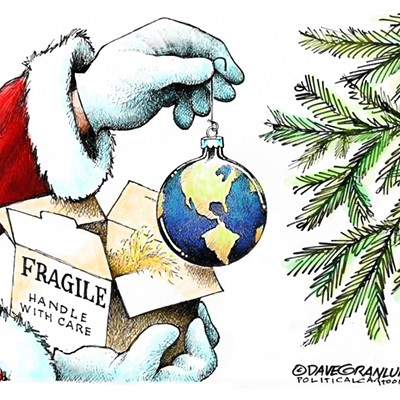

There are so many things to say about September 11, none of them remotely adequate. It's a personal subject for each of us. For myself, I think much more now about my country, and about people around the world who live with the immediate possibility of destruction--the everyday awareness that they, and those they love, are not safe.

We Americans have been like children, in that way. That clear fall morning in New York--has the skyline ever been more beautiful?--a piece of our long childhood came to an end.