Last Friday, I felt a mixture of anger, dismay and profound sadness as I sat and watched the final launch of the United States space shuttle.

I wasn't saddened by the passage of the 30 years since the start of the shuttle program. I wouldn't even be all that bummed out by the sound of chirping crickets in response to the question, "Now what?" What's really sad is that no one inside the government or in the real world is even asking the question, "Now what?"

I am proudly of the generation that got caught up in the initial fervor of the space race. Even as a little kid, it made perfect sense to me when President John F. Kennedy said that the United States would send men to the moon not because it is easy, but because it is hard.

I remember my dad just beaming when he said, "We're going to the moon." My initial thought was, "We don't even own a car; how are we going to go to the moon?" But after he explained it, I understood, and onto the bandwagon I jumped.

What's important was that the "we" made sense. I've always hated it when sports fans use "we" when talking about the successes of favorite sports teams. That's not a "we" thing. The United States going to the moon was a "we" thing. Adult Americans were paying higher taxes without whining all the damn time, and younger Americans were taking as much math and science as possible—all part of the team effort that would get us to the moon! The moon and stars weren't just objects of poetic wanking; they were destinations and challenges to be pursued with vigor in hopes of making us all better, both as individuals and as the human race.

I had knucklehead friends who couldn't name half of the 50 states, but we all knew the names of the seven Mercury astronauts—Shepard, Grissom, Glenn, Cooper, Schirra, Slayton and Carpenter. (If you ever see me on the street, ask me to name them so you'll see that I don't need to Google them. Of course, it might be like that scene in Two Weeks Notice in which lawyer Sandra Bullock gets hit in the head with a tennis ball. In an effort to see if she's OK, Hugh Grant asks her to name the nine members of the Supreme Court. She does so successfully and then asks how she did, to which Grant replies, "How should I know?")

We all took science in the hopes that maybe, someday, we could help mankind take that next step beyond the moon. And we took math in the full understanding that the science of spaceflight was almost entirely mathematical in nature.

These days, people take science in the hopes that they can help a pharmaceutical company get even richer, and they take math hoping to master the more esoteric form of derivatives that help separate retirees from their pensions.

We watched every takeoff and landing of those Mercury astronauts. (The "flights" of Alan Shepard and Gus Grissom lasted only about 15 minutes each and were basically parabolas, like a bullet shot into the air.) John Glenn only orbited the Earth three times, but teachers eagerly incorporated the time of his flight (just less than five hours) into math lessons designed to determine his capsule's speed and altitude.

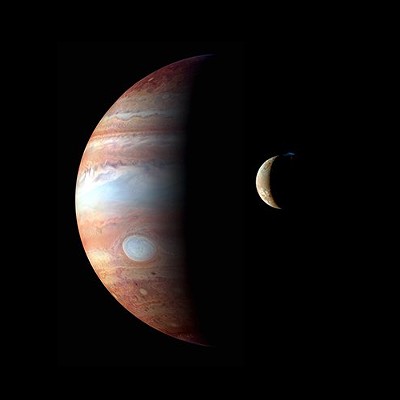

Politics be damned, I marveled at the exploits of the first cosmonaut, Yuri Gagarin, and the first woman in space, Valentina Tereshkova. A little more than a year after John Glenn's first orbital flight, Gordon Cooper stayed in space for a day and a half, competing 22 orbits. The Mercury program was so successful that it was cut short, and it was on to Gemini, with its two-man teams and its electrifying space walks. Then came Apollo and the moon. It's sad knowing that even if I live another 40 years, I probably won't see man walk on Mars.

It is achingly sad to learn that we have basically ceded space to the Russians (and soon, the Chinese). If anything were to go wrong on the space shuttle or the International Space Station, we'll have to hitch a ride with the Russians, at a cost of tens of millions of dollars per astronaut. It is also now mandatory for anyone even thinking about going into space to become fluent in Russian. Doesn't that bother you?

Some claim that private industry will take up the slack, but I don't see it happening. Some make the analogy of what happened in World War II, when industry designed, tested and then mass-produced great planes for the war effort. But back then, corporations had America's best interests at heart. Not so today: I don't think corporations give a crap about America. They care about money—how to get it, how to hoard it and how to keep it from being taxed.

And Washington, D.C.? Congress used to have visionaries; now it has bickerers.

When this final shuttle touches down, even if the pilot has the deftest of touches, it will land with a resounding thud. And we Americans, once the greatest of dreamers and doers, will be earthbound once again.