The American Film Company is a new outfit that promotes itself as making only historically accurate films.

For as long as there have been movies, they've been historically inaccurate, in large part because the truth should never stand in the way of a good story. This collection of filmmakers, however, believes that the stories we have are already good enough.

It's tough to argue that there's no room for historically accurate films in the marketplace. After all, Michael Bay's atrocious Pearl Harbor was more about a love triangle than the attack on Dec. 7, 1941, and worse, it completely downplayed the real contribution of soldiers like Petty Officer Doris Miller, the first African American awarded the Navy Cross (played in the film by Cuba Gooding Jr.), in favor of fictionalized cutouts. Wouldn't a film about Miller be more compelling? Yes, but perhaps not as big of an extravaganza.

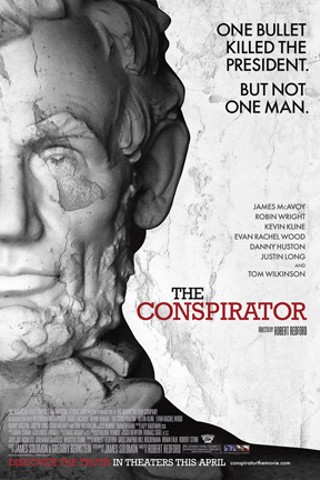

The Conspirator is the American Film Company's maiden voyage, shining a light on the people who helped John Wilkes Booth plan the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, and the people who gave Booth information and shelter afterward. A quick check of Wikipedia reveals that, in fact, Abraham Lincoln was assassinated, so the American Film Company is batting 1.000 to start.

If only the film itself got out of the gate so quickly.

By the time things wrap up, The Conspirator evolves into a thoroughly explained courtroom drama, and if you are unfamiliar with the fate of Mary Surratt, it's a fascinating chapter in U.S. history, presuming this interpretation of events is as close to the real story as possible.

Surratt (Robin Wright) ran a boarding house in Washington, D.C., in 1865, where John Wilkes Booth was a frequent visitor. Surratt's depiction of that scene goes this way: Booth befriended her son, and whatever plans they hatched, she was not privy to them. Surratt also tells her lawyer that her son rode out of D.C. a couple of weeks before the assassination, and she had neither seen nor heard from him since. Nonetheless, the federal government charges Mary Surratt with conspiring to assassinate Lincoln, and puts her on trial in front of a military tribunal instead of a jury of her peers.

If it seems as though the government will hang someone—maybe anyone—for Lincoln's murder, that's because it will. Under the direction of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton (Kevin Kline), a kangaroo court was established to earn a quick conviction and ease the pain of a nation rocked by the assassination hinged on the tail end of the brutal Civil War. Stanton is depicted as a deeply patriotic man, but one to whom the Constitution had limits. It's an interesting stance to take, because while Stanton is as close to a villain as The Conspirator has, at least in terms of propelling the action, it's hard to not sympathize with his actions at a fundamental level.

Defending a seemingly condemned woman is Frederick Aiken (James McAvoy), who had spent the previous four years in battle for the North, and he's opposed to the Southern sympathies of the accused and her alleged associates. If there could ever be a suicide mission for a young attorney, this is it. But Aiken stands firm, both in the face of what he believes to be a railroading of Mary Surratt (guilty or not, she still deserves a fair, untarnished trial) and the possible infringement of the Constitution. If there could ever be a suicide mission worth taking for a young attorney, this is it.

Director Robert Redford comes into this film following the equally political Lions for Lambs, which was a failure. It appears for much of the first hour that The Conspirator might be a repeat performance; the film has no flow while establishing the story, opting instead for a kind of checklist method, rattling off a series of quick facts and major players to pour the foundation for the rest of the story. Well, the rest of the story is fine, and gets much better as it goes, but Redford's impatience with the early events is a real turnoff.

Once the pieces are in place, The Conspirator not only asks some relevant and powerful questions about government's role in protecting the peace and protecting individual liberties, but also shows a lot of flair as a courtroom drama—a genre almost as threadbare as some of this film's period costumes. It's not easy to do either of these tasks, and to accomplish both would be quite a feat.

Well, Redford comes close on both counts. Even forgiving the perfunctory presentation of the trial's background for uninitiated viewers, the rushed nature of the film's final flurry is hard to digest. So carefully does Redford state the case during Surratt's trial that to see so much ground covered over the final 15 minutes is disheartening, to say the least.

Both McAvoy and Wright are quite good, if a little put upon, and Kline is terrific as the rigid Stanton. But Justin Long? The Apple guy looks and acts horribly out of place as Aiken's friend Nicholas Baker. His dialogue and delivery are far too contemporary for the setting, and any scene he's in grinds the film's credibility into putty. It's also such an insignificant role, making it impossible not to wonder why it made the final cut.

In fact, the final cut is probably the biggest hurdle The Conspirator faces: Its opening is fit for a cheap History Channel biography; its ending is rushed; and there a few curious pieces in between. A re-edit is in order.

Or would that be revisionist history?