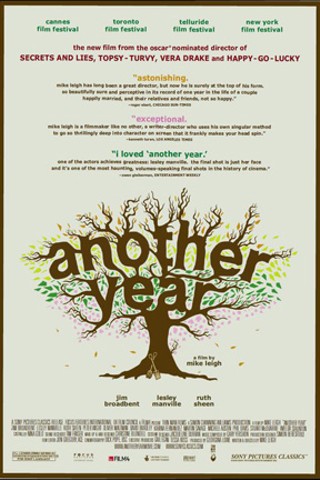

Writer/director Mike Leigh brings together another fine assortment of realistically lived-in characters in Another Year: a therapist and her geologist husband. Her co-worker who is more in need of companionship than her next drink. The couple's son, other friends and relations.

While this is not his best or most memorable work, Leigh's latest is nevertheless very solid and populated with good performances. That has been a familiar refrain since Secrets and Lies in 1996, extending through Topsy-Turvy, Vera Drake and Happy-Go-Lucky.

Another Year doesn't have the special something those films do, however. It is languid, even by Leigh's standard for fairly deliberate storytelling, and some of the people we meet seem too rigidly trapped in their lives, doing the same thing day after day, week after week. And perhaps that is, to some extent, part of Leigh's point, but that doesn't make it entertaining to watch from beginning to end. Of course, that, too, might be part of Leigh's point about other peoples' lives. In any case, this peek into those lives has no clear directive, no concrete beginning, and no conclusion with sweeping impact. You truly have to feel what the characters are going through and let empathy be your guide.

Jim Broadbent and Ruth Sheen play the married Tom and Gerri, around whom the events of Another Year happen most. Unlike the collection of friends who frequent their dinner parties, Tom and Gerri seem perfectly, resolutely happy with their lives. Thanks to 21st-century American cynicism creeping in, we expect one of them to hide bodies in the crawl space or have another family in the city. But no: Tom and Gerri—who offer a good-natured chortle anytime someone points out the fact that they have the same names as the famous cartoon characters—love themselves and each other. They love their friends and their only child. They're just good people through and through, a rarity in the movies.

One of their frequent guests is Mary (Lesley Manville), whose life has been pockmarked by bad choices and her bad reactions to those choices. As Mary, the film's self-immolating spinster, Manville delivers a hell of a portrayal, on par with the best in the Mike Leigh catalog. Playing a Ms. Lonelyhearts without veering into outright caricature is incredibly tough, but Manville strikes familiar chords in an unconventional way and manages to peer out into the abyss without jumping in head-first. That would wreck it.

Desperate for love and friendship, Mary goes for broke each and every time. At the casual mention that she might be a good fit for Tom and Gerri's son, Mary takes the news as if it's a sure thing, so to see her crestfallen when she sees him with another woman is not an easy thing to observe. Manville was not nominated for an Oscar for her work here, although there was significant chatter that she might be. She captivates nearly every moment she's onscreen, particularly during a most peculiar first meeting with the recently widowed Ronnie (David Bradley), a man of exceedingly few words and emotions.

For his efforts here, Leigh did earn another Academy Award nomination (for original screenplay). And it's worth noting that he has more nominations in the past 15 years—seven—than every other filmmaker except for Clint Eastwood, who also has seven, and the Coen brothers, whose collection of envelopes stands at 13. Of course, those tallies include Eastwood's acting and the Coens' editing, plus some Best Picture nominations. The difference is that Leigh works on a much smaller scale and is, somewhat obviously, neither Clint Eastwood nor Joel and Ethan Coen.

It is furthermore worth noting that Leigh's films are built from the ground up through improvisation, which is not to say they're cooked on the spot while the camera rolls. Instead, Leigh develops a sense for the characters over quite a while, then works with incredibly gifted performers to help them build these inventions in a very collaborative environment (over the course of five months of rehearsals, in this case), and allows the actors an almost-unique opportunity to create more lifelike characters.

It clearly works, but this time, Leigh needed a little stronger premise to support them. It could be that there are simply too many characters; Leigh's best films are a little more focused than this, allowing the central characters a broader opportunity to complete their dramatic arc.

Another Year feels a little incomplete, like it could use another year—or at least a few more months.